This is the 15:th post in a series about Microsoft SQL Server R Services, and the 14:th post that drills down into the internal of how it works. To see other posts (including this) in the series, go to SQL Server R Services.

Finally, after a couple of false starts this post will look into the protocol used when transferring data back and forth between SQL Server and the SqlSatellite: Binary eXchange Language (BXL). Why write about it at all? Well, the big reason why I wanted to know more about it, was due to the strange packet sizes I saw when inspecting data being sent from SQL Server to the SqlSatellite: one row with 5 numeric columns had a packet size of 6300 bytes!!!

Before we dive down, let us recap

Recap

That last few Internals blog-posts have all had the same thing in common, discussing data packets going from SQL Server to the SqlSatellite.

In

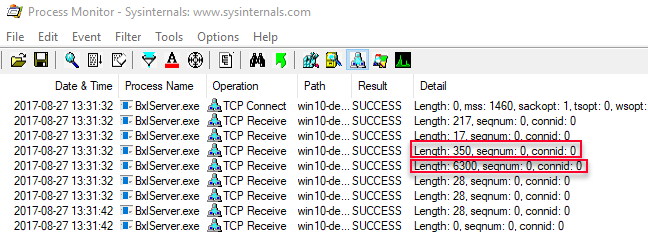

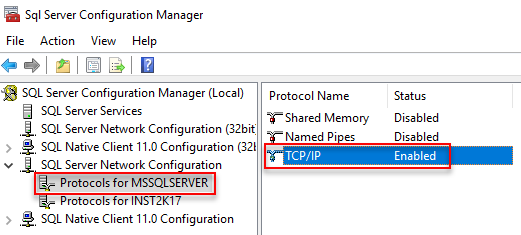

Internals - X we saw how both the external script as well as data from @input_data_1 was sent over a TCP/IP connection to the SqlSatellite from SQL Server, as in the figure below where we see output from Process Monitor:

Figure 1: Process Monitor Output Data Select

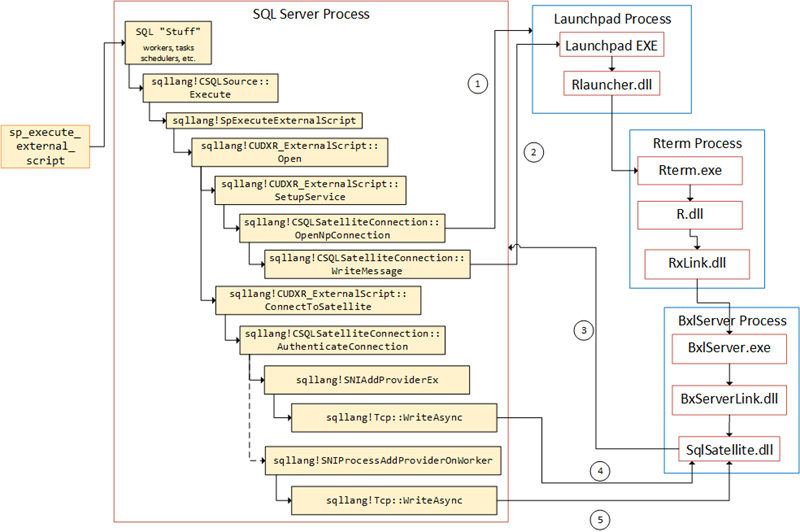

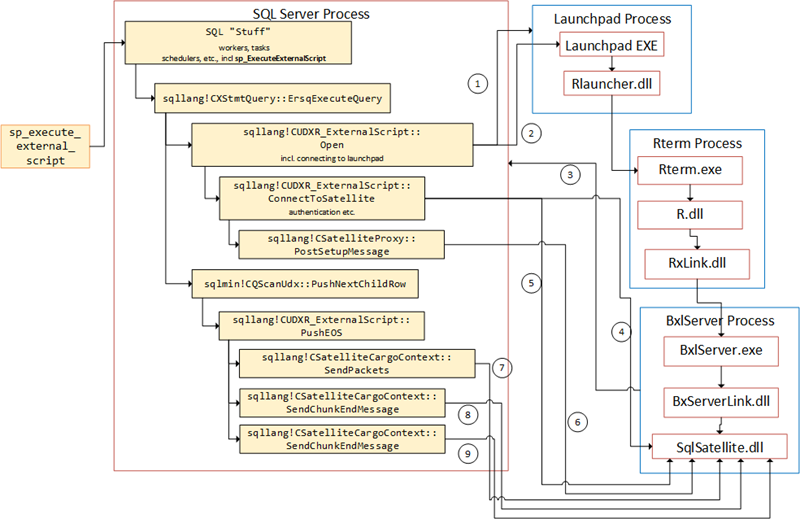

We see in Figure 1 the script packet with a length of 350, and the data packet with a length of 6300 being sent. We also see two packets with a size of 217 and 17 being sent (before the 350 and 6300) and we did not know what those packets were. In Internals - XI we figured out that they were authentication packets sent while the SqlSatelliteConnection was established, and we presented the flow like so:

Figure 2: Flow in SQL Server

In

Internals - XII we looked at at from where the script and data packets are sent (what routines), and we determined that the script packet was sent while the sqllang!CSatelliteProxy::PostSetupMessage routine was called, and the data packet(s) was sent during the sqllang!CSatelliteCargoContext::SendPackets routine. In

XII we also explained the two packets with a length of 28 we see in Figure 1 (being sent after the two data packets), as end packets. Packets used to tell SqlSatellite that no more data is coming. We illustrated the internal SQL Server flow like this:

Figure 3: Flow in SQL Server

Finally in

Internals - XIII we tried to figure out where and when the SELECT statement for @input_data_1 is executed, and we saw the following:

- Before the SqlSatellite was initialized the statement is compiled.

- After the satellite has been initialized the statement is executed.

- If an error happens after the satellite has been initialized, SQL Server sends an abort message to the satellite in the

sqllang!CSQLSatelliteCommunication::SendAbortroutine.

That leads us up to this post, where - as I said above - we’ll look at BXL and why, in Figure 1, we see a packet with a length of 6300, when we just send one row consisting of 5 numeric columns.

Housekeeping

Housekeeping in this context is talking about the tools we’ll use, as well as the code.

Helper Tools

To help us figure out the things we want, we will use Process Monitor, and Microsoft Message Analyzer:

- Process Monitor, will be used it to filter TCP traffic. If you want to refresh your memory about how to do it, we covered that in Internals - X.

- In this post we will use Microsoft Message Analyzer to “sniff” and capture network packets. In Internals - X we used WireShark, but when writing this post I had some issues capturing TDS packets (they were marked as malformed) so I switched to Message Analyzer instead. There is a tutorial here how to use it.

Code

As we did in Internals - XIII we’ll use a database with some specific tables for what we want to do in this post. The code below sets up the database and creates some tables with some data:

|

|

Code Snippet 1: Database, and Database Object Creation

We will also later on in this post create more tables for certain operations.

Protocols

Let us look at what started this investigation; the very big packet size when executing a seemingly innocent statement. In Internals - X we had code looking something like this:

|

|

Code Snippet 2: External Script with Data Select

Yes, yes, I know - the code wasn’t exactly like that, but close enough. When we - in

Internals - X - executed the code we saw this big packet being sent to SqlSatellite. Let us now set up Process Monitor to filter for TCP packets sent to the BxlServer.exe, and execute and see the output from Process Monitor:

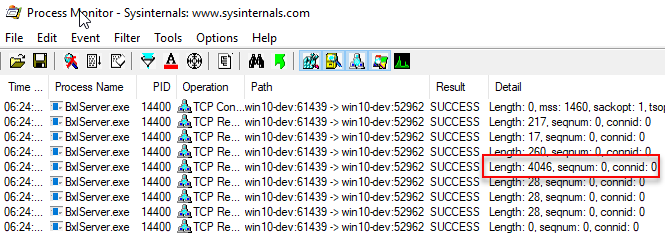

Figure 4: Process Monitor Output

We see now in Figure 4 how we get a very big TCP packet (4046) sent to the SqlSatellite. This packet does contain the data; but 4046 from one row with two integer columns, surely there is something strange going on here? What would the size be if we did a pure SELECT, and didn’t bother sending to SqlSatellite, e.g. we just execute in SSMS? So what we want to do is to execute sp_executesql with the statement in Code Snippet 3, and see what the packet size is:

|

|

Code Snippet 3: Execute sp_executesql

NOTE: We use

sp_executesqlas that is close to what happens when the statement in@input_data_1is executed.

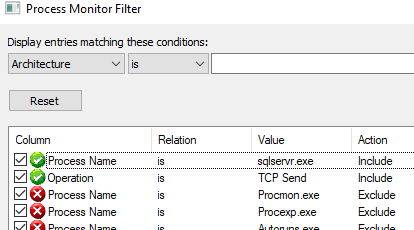

To be able to capture the TCP packets in Process Monitor you need to ensure that the TCP/IP protocol is enabled in SQL Server Network Configuration:

- Open Sql Server Configuration Manager. If it is not in the Apps menu, you can start it up doing a Windows Key + R, and type

SQLServerManager13.mscfollowed by enter. - Expand the SQL Server Network Configuration node, and choose the instance to enable the protocol for.

- Enable the TCP/IP protocol and disable Shared Memory.

On my machine it looks like this, for the default instance:

Figure 5: SQL Server Network Configuration

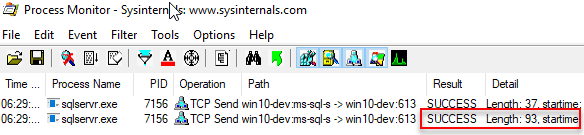

Before you can start see the TCP packets in Process Monitor you need to create a filter to capture these packets, somewhat similar to what you have for the packets being sent to the SqlSatellite:

- Save the existing Process Monitor filter (Filter menu Save Filter) and give it a name.

- Create the new filter as per the figure below:

Figure 6: Filter to Capture TCP Packets

After you have created the filter is a good idea to save that filer as well, so you can switch between filters when needed. Let’s execute the code in Code Snippet 3 and see what Process Monitor outputs:

Figure 7: Packets sp_executesql

In Figure 7 we see two packets being sent, the first one having a length of 37 and the second a length of 93. The second packet is the packet containing the result-set. Compare that to the packet we see in Figure 4 - that’s a big difference; 93 vs. 4043 and the data it contains is the same. So why is this?

The reason we are seeing such a difference come down to what protocol is used for the data transfer. In the case of the data being transferred when executing the code in Code Snippet x, the protocol was Tabular Data Stream (TDS), and we already know that the protocol used for the data in Code Snippet 2 was Binary eXchange Language (BXL).

TDS

This post is about BXL. but let’s mention a bit about TDS so we can later on in this post do some comparisons between these two protocols.

The TDS Protocol is an application-level protocol used for the transfer of requests and responses between clients and database server systems. It allows for most actions that can happen between a client and server:

- Authentication and identification.

- Issuing of SQL batches, stored procedure calls, etc.

- Transaction manager requests.

- Returning data. The returned data is self-describing and record-oriented.

When we executed the code in Code Snippet 3, (apart from authentication packets etc.) a packet would have been sent from the client (SSMS) with the request to execute the statement, followed by a response from SQL Server with the result data (that was the packet with a length of 93). The client receives the data and parses it based on the meta-data in the return packet.

If you want to know more about TDS, it is quite well documented and the internet has quite a lot of information floating around. Even though there are quite a lot of information around, seeing that this series is a lot abut “spelunking”, let’s see if we can learn something about the TDS protocol by using the tools we have at hand.

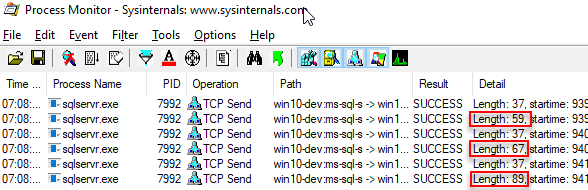

We’ll start with Process Monitor and look at packet sizes. The code you executed in Code Snippet 3, executed against the dbo.rand_1M_N table, where the columns are nullable. To not be “led astray” by null values, etc., we’ll now use the dbo.rand_1M table where all columns are constrained to be non null (in all other aspects the table looks exactly the same as dbo.rand_1M_N). So:

- Ensure that the filter you created in Figure 6 is loaded in Process Monitor

- Clear the display.

Now you can execute the code in Code Snippet 4 below:

|

|

Code Snippet 4: Execute Against Non-Nullable

The idea with the code in Code Snippet 4 is that you can see if there are any differences in the packet lengths, and from there potentially make some assumptions about the packets, The output when I execute looks like so:

Figure 8: Multiple Executions

We can immediately see a difference between the first statement where we retrieve y (length 59) and the second where we get rand1 (67). Both columns are non nullable integers, so part of the difference must be the column name length. So, in TDS result packets the column names are returned in the packet, and they are returned as unicode (double byte). When comparing first and second statement, the second statement’s column name is 4 character longer than the first, so 8 bytes - and that would explain the difference.

On to second and third statement. Third statement returns an additional column, where the size of the column is 4 bytes (integer) and the column name adds 10 bytes (length of rand2 * 2). That gives us 14 bytes, and we now have 8 bytes un-accounted for. Those 8 bytes are for the column header, e.g. each column has a header of 8 bytes. As we have seen, the column header does not include the column name, but the column name is included in addition to the header.

The code above retrieves 1 row - what about multiple rows, will we get column headers etc. again? To check this, execute SELECT TOP(2) rand1, rand2 ... and look at the packet length. When I execute that particular code I get a packet length of 98, e.g. 9 bytes more than for one record. We can definitely say that no new column headers are included . But why 98 bytes, I would have expected 97: i.e. 89 plus two integer column values of 4 bytes each? It looks like each row in the TDS result packet has an additional byte added to it.

Based on all this, it seems that there may be some additional data in the TDS result packets, seeing that the first statement resulted in a packet with the length of 59. Let’s sum up the parts for the first statement:

- Data type size - 4

- Column header - 8

- Column name - 2

- Row byte - 1

That gives us a total of 15 bytes, which means there is an extra 44 bytes in the packet - somewhere. Where those bytes are, is not of interest for this discussion, but what is interesting is what the packet looks like.

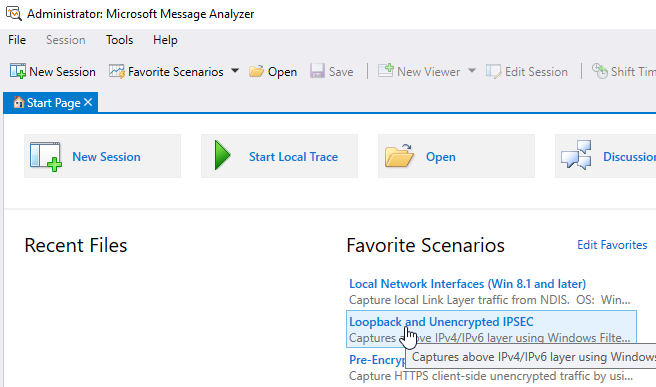

For this we’ll use Microsoft Message Analyzer (MMA). To use MMA we need to shut down Process Monitor first, and after Process Monitor is shut down, let’s start up MMA as admin. After you have started MMA, here is what you do:

- Initialize a new “packet capture” session by clicking on the Loopback and Unencrypted IPSEC scenario as below:

Figure 9: Microsoft Message Analyzer

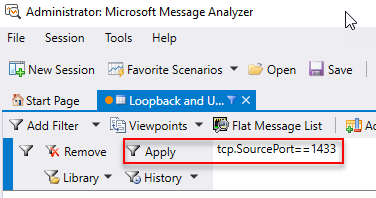

- Set a filter, where the filter is the source port for the packets:

tcp.SourcePort==1433(we are using SQL Server’s default port), and click Apply:

Figure 10: MMA Filter

The capture session has started and you’ll see messages being captured. To not “clutter” the screen you can stop capturing either from the Session menu, or the stop button in the menu bar, or by pressing Shift + F5.

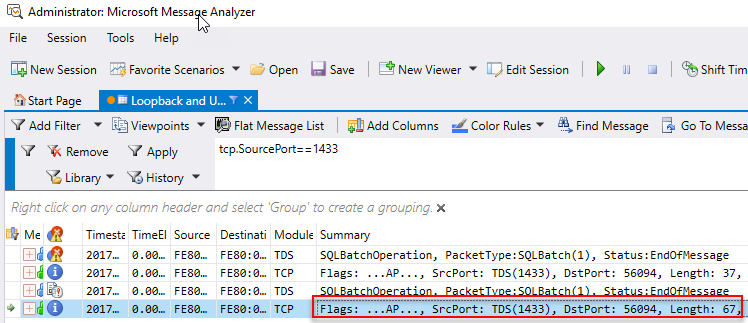

To “clear” the display start capturing again (F5), and then execute sp_executesql N'SELECT TOP(1) rand1 FROM dbo.rand_1M' and see what MMA captures:

Figure 11: MMA Capture

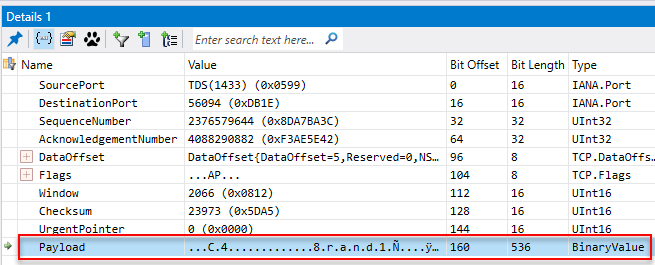

In Figure 11 we see how MMA has captured some packets, and we are interested in the last row - where we in the Summary column see a length of 67. When we click on that row, the Details 1 window looks like so:

Figure 12: Packet Details

In Figure 12 we see how we have clicked on the Payload entry, and by right clicking in the Value column we can copy out the binary value of the packet.

|

|

Code Snippet 5: Binary Packet - 1 Row 1 Column

In Code Snippet 5 we see how the column name is printed out in clear text, but the rest is fairly hard to make sense of. One thing we can assume though is that each character (or dot) represents a byte. To try and make things a little bit clearer, let’s execute against a table with varchar(4) columns: dbo.tb_Test1. Reason for executing against varchar columns is that the column value is output in clear-text, and that might make it easier to see what is going on.

NOTE: I choose

varchar(4) NOT NULLas column types, to make it as close to an integer - which we have looked at up until now - as possible.

The statements we’ll execute are the following:

SELECT TOP(1) rand1 FROM dbo.tb_Test1SELECT TOP(1) rand1, rand2 FROM dbo.tb_Test1SELECT TOP(2) rand1, rand2 FROM dbo.tb_Test1

This is what the captured binary packets look like on my machine when I execute the statements above:

|

|

Code Snippet 6: Binary Packets - 1 Row 1 Column, 1 Row 2 Columns, 2 Rows 2 Columns

From Code Snippet 6 above we see how the column values are printed in clear-text, and to make the copied values somewhat clearer I have entered a new-line after the last column name. What is common between the binary values in all packets in both Code Snippet 5 and Code Snippet 6, is that the last part starts with the ÿ character, and it directly follows the last column value. It definitely looks like the ÿ..Á.........y....þ..à......... sequence defines the end.

NOTE: It turns out that the assumption about the

ÿsequence is correct. If we were to execute a statement that resulted in multiple TDS packets, only the last packet would have theÿsequence.

When looking at Ñ character and what comes after it, we see in Code Snippet 5 how there are 4 bytes (dots) after the Ñ, and in the first packet in Code Snippet 6 there are 2 dots followed by the data in the column (size). In both cases it is followed by the ÿ sequence. For the other statements in Code Snippet 6 we also see those two dots (bytes) preceding the column text. These two bytes defines the size of the variable length data, and those bytes are per variable length column.

Looking some more at the Ñ character, wee see how it precedes the column values. In the first instance we had one row one column (2 bytes + 4 bytes), and in the second 2 columns and one row (12 bytes total). So to me it looks like the Ñ character is the start of a row, which would fit in with what we said abut each row had one byte added to it. When we look at the last packet (in Code Snippet 6), we see that our assumptions seem fairly accurate. That packet represents 2 rows, 2 columns, and we see 2 Ñ followed by the two column values each, with a final ÿ sequence. In essence, the result TDS packet looks something like this using the last packet in Code Snippet 6:

|

|

Code Snippet 7: TDS Packet

From what we have seen so far and what we see in Code Snippet 7, we can deduce that TDS is a row based protocol; there is a header-like initial part containing, among other things, column information. This is followed by the individual rows, and finally there is an end section.

Phew, that was quite a bit about TDS. Hopefully, having covered this - it will help us in understanding BXL, or at least do comparisons.

Binary eXchange Language (BXL)

Right, so back to what this post is all about - BXL. When Microsoft came up with Microsoft R Server / SQL Server R Services, BxlServer and SqlSatellite, they realized that using TDS for data transfers were not the most optimal way to do transfers. The reason being that TDS is basically a request response protocol, where the “client”:

- Sends a request to the server

- Receives responses from a request.

- Parses the response.

- Asks for more data, until the server indicates there are no more data.

In the case of SQL Server R Services, the SqlSatellite is not doing a request, but the SQL Server pushes data to the SqlSatellite, and it wants to do is as efficient as possible. That’s the reason (at least one of them) why Microsoft introduced BXL, where BXL is optimized for fast data transfers between SQL Server and external script engines.

Right now you probably think: “what is he talking about, transferring a packet of 4043 bytes (as above) does not seem efficient?!”. No, you are right - but as we’ll see, this is not always the case. For example, if we were to execute the statement in Code Snippet 2, but instead of against dbo.rand1M_N we do it against dbo.rand1M (the table we have used for the TDS examples), what would the output from Process Monitor be? The code would look like so:

|

|

Code Snippet 7: External Script Non-Null Table

Shut down MMA and open Process Monitor again (as admin) and load the filter you saved to filter against BxlServer. When you execute the code in Code Snippet 7 you’ll see Process Monitor reporting a packet size of 72 bytes! Hmm, 72 bytes vs. 4043 - what is going on? The only difference is that the columns in dbo.rand_1M are constrained to be not nullable, so it seems that a nullable column has a huge impact on packet sizes for BXL.

Packet Layout

OK, let’s see if we can figure out the format of a BXL packet, and we’ll do it in more or less the same way we did TDS packets above. So take the SQL statements in Code Snippet 4, and execute through sp_execute_external_script, and for each statement capture the packet size. When I do it I get following packet sizes:

SELECT TOP(1) y FROM dbo.rand_1M- 36SELECT TOP(1) rand1 FROM dbo.rand_1M- 36SELECT TOP(1) rand1, rand2 FROM dbo.rand_1M- 72

As we see in the list above, both statement 1 and statement 2 resulted in a same size packet. So it seems that column names do not have any impact on the size of the actual result packet being sent to SqlSatellite, e.g. they are not included in the packet. That sort of makes sense, since we in Internals - X saw how the column names are being sent to the SqlSatellite in the script packet.

Interesting is the size of the resulting packet for the third statement - it is twice the size of the packet for both the first and second statement! Is it a co-incidence that the third statement has two columns, where the two first statements have only one? To test that out, execute sp_execute_external_script as before but with the statement: SELECT TOP(1) rand1, rand2, rand3 FROM dbo.rand_1M, and see the packet size. The packet size comes out at 108 bytes, 3 times the size of the packet returning one row, one column. So it seems that each column “weighs” in at 36 bytes (including the data type size). So what about if there are more rows than one: SELECT TOP(2) rand1, rand2 FROM dbo.rand_1M, what will the packet size be? Ah, that returns a packet size of 80, 8 bytes more than for one row. So for a row, the size increase is for only the size of the data, no extra bytes for rows etc.

NOTE: The above statement is true at least for non-nullable columns and fixed width data types.

Given that one row, one column (integer) had size of 36, it seems that each column has an overhead of 32 bytes. Seeing what we’ve seen so far, it looks like there is a difference in packet format between TDS and BXL, so let’s do what we did with TDS and have a look at what the binary packets look like.

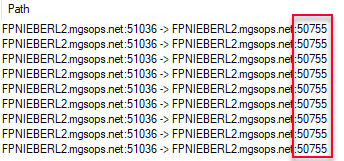

Execute the statements in Code Snippet 6, but do it with sp_execute_external_script instead, like in Code Snippet 7. Capture the response packets with MMA like we did for TDS and see what they look like. This time when we filter the TCP, we need to do it on the SQL Server source port that listens on for the satellite connection. The easiest way to get that port number is to look at the Path column in Process Monitor:

Figure 13: Get Port Number from Path

Equipped with the port number we can now execute the statements we used in Code Snippet 6 (but with sp_execute_external_script), plus an added statement and see what the response packets look like, and also the sizes. The added statement is SELECT TOP(2) rand1 FROM dbo.tb_Test1 and we should execute it as second statement in the “batch”. When I execute the four statements I get following packets and packet sizes:

|

|

Code Snippet 8: BXL Binary Packets

This looks quite different from TDS. In TDS we saw a header with column information followed by rows of data followed by an end sequence. In BXL we get column oriented data, e.g. each row appears together with the column, and we are not seeing an end sequence. So whereby TDS is a row oriented protocol, BXL seems to be column oriented.

Notice how the packet sizes for the results returned from the statements against the varchar columns are slightly bigger than from the int columns (38 vs. 36, 76 vs. 72). This is - as in TDS - due to each varchar column is preceded with 2 bytes, indicating data length. With that in mind, we see again how each column has a 32 bytes overhead, like a column header. What is in that column header then? Well, since BXL is not documented, it is hard to tell - my guess is that the header contains column information such as data type, maybe number of rows, potentially whether the column is nullable, etc.

So, if the column header is 32 bytes, what is the storage size for each column (we have already mentioned that varchar seems to require more storage)? I did some testing by creating a table with one not nullable column each, for interesting data types (I started with numeric types), and inserted two rows per column into the table:

NOTE: Below we’ll see why two rows.

|

|

Code Snippet 9: Numeric Types Table

I then executed sp_execute_external_script with a SELECT TOP(1) column_name ... followed by a SELECT TOP(2) column_name ... statement and noted the packet size in Process Monitor. Finally I compared the packet sizes, and tried to determine the size of the column in terms of storage.

For the data types in the table in Code Snippet 9 I came up with the following:

| Data Type | Column Data Size | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| tinyint | 1 | - |

| smallint | 2 | - |

| int | 4 | - |

| bigint | 8 | - |

| decimal / numeric | 1 + (5 | 9 | 13 | 17) | Size based on the precision. My assumption is that the pre-pended byte defines the precision (but I am not sure). |

| float | 4 | 8 | Size based on number of bits that are used to store the mantissa of the float number in scientific notation. |

| real | 4 | - |

| money | 4 | - |

Table 1: Column Data Type Storage Size

What we see in Table 1 is fairly straight forward, the only slightly confusing thing is the pre-pended byte on a decimal or numeric column.

Even though you probably won’t send that much alpha-numeric data to the SqlSatellite, I did a similar test for alpha-numeric data types:

|

|

Code Snippet 10: Character Types Table

I executed in the same way as for the numeric types and arrived at the following:

- The header was 32 bytes.

- Columns of alpha numeric type all had 2 bytes pre-pended to the bytes, except

maxtypes (see below). - For

charandncharthe storage size was 2 bytes plus the size the column was defined as. - For

varcharandnvarcharthe storage size was 2 bytes plus the size of the data stored.

For varchar(max) (which was the only varmax type I checked against), the story was somewhat different:

- The header was 32 bytes.

- For a data-size up to 4000 bytes, 4 bytes were pre-pended

- When the data size exceeded 4000, the number of pre-pended bytes increased exponentially.

Why the varmax types behaved as they did I am not sure, but for now I’ll leave it at that. It may become a topic for a future post.

Nullable Columns

Nullable columns, yes. As I’ve said before, this post originated due to me seeing very strange packet sizes when sending data from SQL Server to the SqlSatellite; like in Figure 4. We saw then, in this post, how this was due to accessing data from nullable columns (in the beginning of the BXL section).

Trying to figure out why nullable columns were different, I created a new test table, like dbo.test3, but this time with nullable columns:

|

|

Code Snippet 11: Nullable Numeric Table

When executing as before (two statements per column), the packet sizes were as follows:

| Data Type | 1 Row | 2 Rows | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| tinyint | 7313 | 7314 | - |

| smallint | 3889 | 3891 | - |

| int | 2023 | 2027 | - |

| real | 2023 | 2027 | - |

| float | 2023 | 1050 | 2027 | 1058 | Based on storage size 4 or 8 bytes |

| bigint | 1050 | 1058 | |

| money | 1050 | 1058 |

Table 2: Nullable Packet Sizes

Wow, what we see in Table 2 is - to put it mildly - weird! Three things stand out:

- If we subtract the size of the data type, we get the overhead, as we did with non nullable types. But for nullable types, the overhead is different between data types, and it is related to the underlying data type.

- The overhead is greater for smaller data types!

- Where are

decimal/numeric?

The reason decimal is not in Table 2, is that when I ran the statements against the nullable decimal columns I got exactly the same result as for non nullable decimal! So for decimal, being nullable or not has no impact!

By now I was utterly confused (more than usual), and decided to create a table like dbo.test4, but instead of the columns being non-nullable, they should be nullable. I then ran the same statement against that table as I did against dbo.test4 to see the packet sizes for alpha-numeric nullable columns. The result did not differ anything from when I ran against dbo.test4! E.g. the behavior were the same as for decimal. I feel a headache coming on, so this is it for now!

Summary

The purpose of this post was to get some insight into the Binary eXchange Language protocol, used by SQL Server to send data to the SqlSatellite. We saw how the protocol moves data in column oriented fashion, and the protocol utilizes schema information to optimize how to send the data.

When looking at the data sent, the size of the packages and “drilling” into the TCP packets we could deduct that: :

- Each column has an over-head of 32 bytes (at least for non nullable data)

- The size of the column in one row is the size of the data type for numeric types.

- For

decimalandnumerican extra byte is added to each column, where this byte indicates the precision. - Columns of alpha numeric type all had 2 bytes pre-pended to the bytes, except

maxtypes. - For

charandncharthe storage size was 2 bytes plus the size the column was defined as. - For

varcharandnvarcharthe storage size was 2 bytes plus the size of the data stored. - For the

varmaxdata types the number of bytes that were pre-pended varied dependent on the data size.

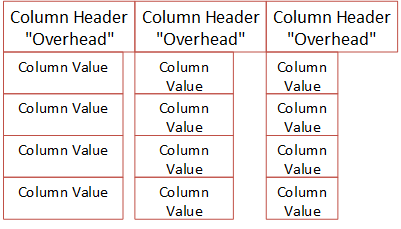

Not taking into account bytes pre-pended to a column etc., the diagram below tries to illustrate the layout of a BXL packet:

Figure 14: BXL Schematic Layout

Figure 14 shows what a BXL packet can look like. In this case it is a three column, four row packet. We see how the column headers all have the same size, where the individual columns can vary in size - but it will still fit into the size of the header.

What happens with nullable columns is a mystery, as we saw column overheads ranging from 7312 bytes (tinyint) to 32 bytes (decimal). I can’t help but think that there is a “bug” in there somewhere that causes this, and I will try and follow up with Microsoft regarding this.

Regardless of that, I will do some more playing around investigations around BXL, so there will most likely be a second post about BXL after this one.

~ Finally

If you have comments, questions etc., please comment on this post or ping me.

comments powered by Disqus