This is the 16:th post in a series about Microsoft SQL Server R Services, and the 15:th post that drills down into the internal of how it works. To see other posts (including this) in the series, go to SQL Server R Services.

In the last post Internals - XIV we looked at the Binary eXchange Protocol (BXL). The post was fairly long, and there were things that I wanted to cover which I didn’t do due to the length of the post.

So this post is a continuation of Internals - XIV.

Before we dive into it, let’s recap what we covered in Internals - XIV.

Recap

After many attempts, I finally managed to do the post about BXL. To my defense I’d like to say that the “failed” attempts led to other posts instead :).

In

Internals - XIV we started looking at TDS, which is an application-level protocol and THE protocol used by SQL Server for the transfer of requests and responses between clients and database server systems. We tried to get an understanding for how a TDS response packet looked, and executed against a table: dbo.tb_Test1 and retrieved some integer columns: sp_executesql N'SELECT TOP(2) rand1, rand2 FROM dbo.tb_Test1'. By using Microsoft Message Analyzer (MMA), we saw that the packet looked like so (the values of all the columns are size):

|

|

Code Snippet 1: TDS Packet

From the above, and also looking at the package length, we determined that TDS response packets were row oriented, with a header part consisting of - among other things:

- Column headers followed by the column name for each column.

- After the headers, rows followed, where each row had a row delimiter (the

Ñcharacter in Code Snippet 1). The rows contained the individual column values. - As last part of the packet was an end sequence. This is reflected in Code Snippet 1 as the line starting with

ÿ. This only appears in the last packet of results.

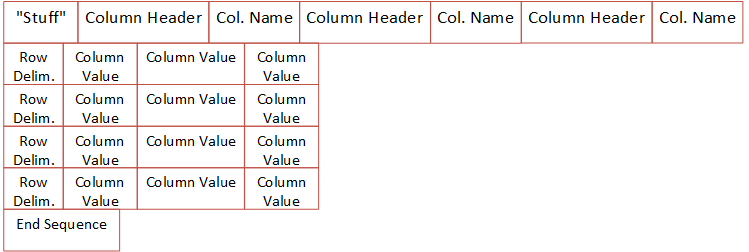

The TDS layout can be illustrated as so:

Figure 1: TDS Packet Layout

In Figure 1 we see a TDS packet with three columns, four rows and an end sequence.

We then went on to BXL, which was introduced by Microsoft to be a protocol optimized for fast data transfers between SQL Server and external script engines. We executed the same code as what we did for the result in Code Snippet 1, and - in MMA we saw a packet like so:

|

|

Code Snippet 2: Layout of a BXL Packet

By looking at Code Snippet 2, we saw how BXL is a column oriented protocol, with a header of fixed size for each column, followed by the rows for that column. In Internals - XIV we came to the conclusion:

- Each column header has an over-head of 32 bytes (at least for non nullable data)

- The size of the column in one row is the size of the data type for numeric types.

- For

decimalandnumerican extra byte is added to each column, where this byte indicates the precision. - Columns of alpha numeric type all had 2 bytes pre-pended to the bytes, except

maxtypes. - For

charandncharthe storage size was 2 bytes plus the size the column was defined as. - For

varcharandnvarcharthe storage size was 2 bytes plus the size of the data stored. - For the

varmaxdata types the number of bytes that were pre-pended varied dependent on the data size.

Nullable columns were somewhat weird in that the header for each column ranged from 7312 bytes for tinyint down to 32 bytes for decimal/numeric and alpha-numeric types. In

Internals - XIV I speculated that this is some sort of bug, but I haven’t been able to verify that yet.

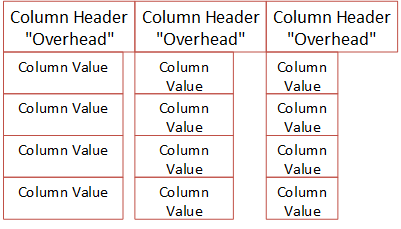

Finally I tried to show the layout of BXL as so:

Figure 2: BXL Schematic Layout

Figure 2 illustrates a three column, four row packet. We see how the column headers all have the same size, where the individual columns can vary in size - but it will still fit into the size of the header.

Housekeeping

Housekeeping in this context is talking about the tools we’ll use, as well as the code. Oh, I’ve had a couple of questions why I have this section here - this is meant to be for you guys who want to follow along in what we’re doing in the posts.

Helper Tools

To help us figure out the things we want, we will use Process Monitor, and WinDbg preview:

- Process Monitor, will be used it to filter TCP traffic. If you want to refresh your memory about how to do it, we covered that in Internals - X.

- WinDbg preview is a windows debugger, which Microsoft released in August as a preview version of a more modern WinDbg application. If you want to know more about it, I covered it in Internals - XII. Throughout this post I will refer to it as WinDbg.

Code

The code below sets up the database and creates some tables with some data, it is more or less the same as we used in Internals - XIV:

|

|

Code Snippet 3: Database, and Database Object Creation

So if you want to follow along with what we do in this post, run the code in Code Snippet 3, and you should be good to go.

Lots of Data

In Internals - XIV we saw how a packet was structured (both BXL and TDS), and the size of a packet when the packet returned just a couple of rows. Let’s look at how BXL handles large data volumes and compare it to TDS. Let’s start with TDS.

TDS

Remember how I, in the previous post, said that the TDS protocol is basically a request response protocol, where the “client”:

- Sends a request to the server

- Receives responses from a request.

- Parses the response.

- Asks for more data, until the server indicates there are no more data.

The last bullet point above: “Asks for more …”, indicates that there is a limit to how much data the server sends to the client in one go, and by default that limit is the size of a network packet: 4096 bytes. We can see this if we fire up Process Monitor and set a filter capturing outgoing TCP packets from SQL Server.

NOTE: We covered in Internals - XIV how to set that filter. There we also spoke about how the TCP/IP protocol needs to be enabled in SQL Server Network Configuration.

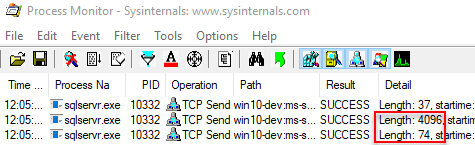

After you have set the filter (and saved it), execute sp_executesql N'SELECT TOP(820) rand1 FROM dbo.rand_1M' and look at the output from Process Monitor:

Figure 3: Multiple Packets

Figure 3 shows how we receive two response packets, one with a size of 4096 bytes, and the other with 74, so a total of 4170 bytes. But wait a second, if we go back to Internals - XIV and read what was said about packet sizes, I would have expected to see:

- 44 bytes, some miscellaneous overhead (including end sequence).

- 8 bytes column info overhead.

- 10 bytes column name (5 characters * 2).

- 3280 bytes for row data (820 * 4).

- 820 bytes (1 byte row delimiter per row).

This according to my math would total up to 4162 bytes, why 8 bytes more? Reason for the 8 bytes is that each extra packet has an 8 byte header. This is regardless of of number of columns.

Now we have confirmed that TDS indeed returns packets in network packet size, what about BXL?

BXL

Let’s see what the result is when executing the above in sp_execute_external_script:

|

|

Code Snippet 4: Large Resultset in BXL

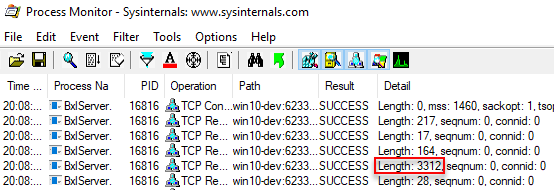

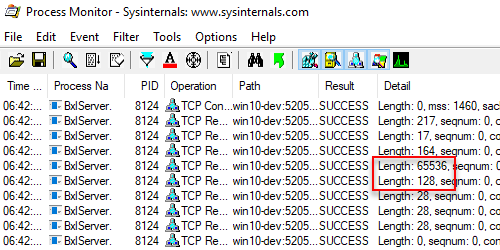

Before executing the code in Code Snippet 4 we need to change the Process Monitor filter to on TCP packets received by BxlServer, like we did in Internals - XIV. After that is done we can execute and look at the output from Process Monitor:

Figure 4: BXL Packet 820 Rows

There are a couple of things to notice from the output we see in Figure 4:

- Only one response packet has been sent from SQL Server to the SqlSatellite (length 3312).

- The packet is smaller than the total size of the TDS packets in Figure 3 (4170).

Right, this test didn’t do anything else than show us that this BXL packet was smaller than its TDS counterpart. Remember in BXL we have the 32 bytes overhead followed by the rows, where in TDS there are column names, row delimiters, end sequence etc. It would make sense for the BXL packet to be smaller, at least for a narrow (few columns) result.

So what if we executed it with a a TOP clause that is bigger? What is the output if we execute the code in Code Snippet 4 with TOP(2000) instead? Once again only one packet, this time with a size of 8032 bytes. OK, so BXL is not doing network size packets, but at one stage or another there has to be more than 1 packet - sending gigs of data in one packet wouldn’t make sense?! Let’s try TOP(5000), that should result in a total of 20032 bytes, and probably more than one packet. No, still only one packet, and the size is 20032. Let’s “go wild” and do TOP(16400):

Figure 5: BXL Packet 16400 Rows

Finally, that gives us more than one packet and in Figure 5 we see two packets: one with a size of 65536, and one with a size of 128. So it looks like the “cutoff” for more packets is at 65536 bytes.

NOTE: 65,536 is considered a significant number. It is the product of 2 to the power of 16. Why use this particular product? Because it is the largest number that can be expressed by 2 eight-bit bytes of data.

The total size of the two packets in Figure 5 is 65664 bytes. However the row size for the 16400 rows is 65600 bytes, so these two packets have 32 bytes “extra”. That should not be a surprise as we have previously said how a packet has a 32 bytes “overhead”/header per column, and this column header is per packet.

NOTE: As we’ll soon see, I lied a little when I said the overhead was per packet.

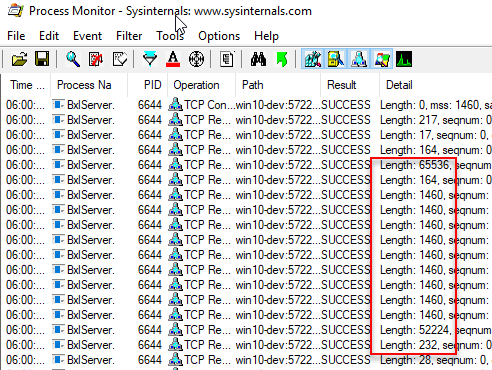

OK, so what happens if we were to send some more data, let’s do TOP(32800):

Figure 6: BXL Packet 32800 Rows

What is highlighted in Figure 6 are the data packets sent to SqlSatellite, and as we can see they are quite a few. In fact, there are 13 of them including the first with a size of 65536. If we added the size of all the packets it would add up to 131296 bytes. With 13 packets, and each carrying a column overhead of 32 bytes the total row size would be 130880 (131296 - (13 * 32)). But, when we calculate the actual size (32800 rows * 4) we arrive at 131200? All of a sudden the actual size is greater than what we expect based on the packet sizes. So maybe what I said above, about the column overhead being per packet, is not correct.

If we look at total size from the packets (131296) and the actual row size (131200) we see the difference being 96 bytes. We know that the two first packets carry an overhead of 32 bytes, so that leaves us with another 32 bytes to explain. The explanation is that the column overhead is per packet of 65536 bytes (or thereabouts), and if we were to add up the packet sizes starting with the packet of 164 bytes, and end at the packet with a size of 52224, we’ll end up with 65528 bytes. So we have in essence two packets with a size of ~65536 bytes and a final packet weighing in at 232 bytes, and the 232 bytes packet contains a 32 byte overhead.

NOTE: The reason we’re not getting 65536 bytes exactly in the second packet is due to how the individual packets are sent, and how Process Monitor reports it.

To get a better understanding how this works, let us do some spelunking in the SQL Server code with WinDbg.

WinDbg Debugging

Whet we’ll do here is to figure out some of the flow when creating the packages that are being sent to SqlSatellite, and well do this by setting breakpoints in WinDbg and tracing what’s happening when we hit those breakpoints.

In

Internals - XIII we figured out when and how the statement in @input_data_1 was executed, and we saw a flow looking something like so:

|

|

Code Snippet 5: Abbreviated Flow Result Data

Let’s do this:

- Start up WinDbg as admin.

- Attach to the SQL Server process.

- Set breakpoints at

sqlmin!CQScanUdx::PushNextChildRowandsqllang!CSatelliteCargoContext::SendPackets.

When the breakpoints are set, execute following code, and see what breakpoints are being hit:

|

|

Code Snippet 6: Test Statement

We are selecting 2 rows in Code Snippet 6, just to see how many times sqlmin!CQScanUdx::PushNextChildRow and sqllang!CSatelliteCargoContext::SendPackets are called. When executing you’ll see sqlmin!CQScanUdx::PushNextChildRow and sqllang!CSatelliteCargoContext::SendPackets being called once. So whatever happens must happen between those two calls. Now, disable the break-point at sqllang!CSatelliteCargoContext::SendPackets and execute again. At this time when you hit the sqlmin!CQScanUdx::PushNextChildRow break-point, instead of continuing do a wt -l6 and see what is being output.

NOTE: As covered in a couple of other Internals posts

wtstands for “watch and trace”. When you execute this command at the beginning of a function call, the command runs through the function and then displays statistics. The options-lindicates how many levels deep to trace. So above we say that we want to trace 6 levels deep.

The output is quite “chunky” (I see the odd 355 rows). We are not interested in every little detail, but something that would give us clues about how data is written to the data packets.

|

|

Code Snippet 7: Flow of Posting Data

I will not go into detail of the trace, but in the trace we see some interesting routines. We’ll set breakpoints at these routines (in addition to the break-point at sqlmin!CQScanUdx::PushNextChildRow), in order to try to understand how it all works:

bp sqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript::PushRow.bp sqllang!CServerCargoContext::PostOneRow.bp sqllang!CSQLSatelliteMessageDataChunk::WritePayloadHeader.bp sqllang!CSQLSatelliteMessageDataChunk::WriteData.bp sqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript::PushEOSbp sqllang!CSQLSatelliteMessageDataChunk::WriteMessageBlockDone.- Re-enable the break-point at

sqllang!CSatelliteCargoContext::SendPackets.

When we execute the code in Code Snippet 6 again, we break at the various break-points like so:

|

|

Code Snippet 8: Break-points Hit when Executing

The code in Code Snippet 6 selects one column two rows, and in Code Snippet 8 we see how PushRow and PostOneRow is called twice. The routine WriteData is also called twice, but WritePayloadHeader only once. We see how WriteMessageBlockDone is called once as part of PushEOS (we discussed PushEOS in

Internals - XII) , and then finally SendPackets. It is pretty clear that PushRow and PostOneRow is called per row in the result-set, and WritePayloadHeader only once. The question now is what happens if more than one packet is sent? To see this, change the TOP clause in the @input_data_1 statement to be TOP(32800), and execute. Wait, wait, before executing disable the PushRow, PostOneRow and WriteData break-points, unless you want to press F5 or g 32800 times.

The execution with TOP(32800) hits the break-points as so:

|

|

Code Snippet 9: Break-points when Executing 32800 Rows

The output we see in Code Snippet 9 is for the same statement whose packets were illustrated in Figure 6. There we had two big packets, and some small packets being sent, and we initially thought that there was a packet header for each packet - but when calculating sizes, we realized it couldn’t be. What we now see in Code Snippet 9 collaborates that, where we see WritePayloadHeader being called three times, which fits in with what we determined above.

The WriteMessageBlockDone routine is interesting in the sense that what does it write, and where does it write to. The immediate thought would be that it would write it as an end “blob” in the packet, but if you remember from [Internals - XIV] where we looked at the the binary representation of a BXL packet where we had selected against a table with alpha-numeric columns, we saw a packet structure like so:

|

|

Code Snippet 10: BXL Binary Packets

We selected one column, and row and as we see in Code Snippet 10, the row value is “size”. When looking at Code Snippet 10 we do not see anything in the packet after the value, which then tells us that if WriteMessageBlockDone writes anything to the packet, it has to be to the header.

In all the examples in this post we’ve retrieved only one column. What does it look like if we are selecting more than one? Re-enable the breakpoints we used when we executed what resulted in the output in Code Snippet 8:

bp sqlmin!CQScanUdx::PushNextChildRow.bp sqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript::PushRow.bp sqllang!CServerCargoContext::PostOneRow.bp sqllang!CSQLSatelliteMessageDataChunk::WritePayloadHeader.bp sqllang!CSQLSatelliteMessageDataChunk::WriteData.bp sqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript::PushEOSbp sqllang!CSQLSatelliteMessageDataChunk::WriteMessageBlockDone.bp sqllang!CSatelliteCargoContext::SendPackets.

Change the @input_data_1 statement in Code Snippet 6 to SELECT TOP(2) rand1, rand2 FROM dbo.rand_1M and execute. You’ll see how we’re looping over the rows, and for each row we’re looping the columns, for first row we write the header and the value and for subsequent columns the value.

Summary

This post was a continuation of Internals - XIV, where we in this post looked at subjects that did not “fit in”, in the XIV post.

We looked at the size of packages and compared it with TDS, and saw how TDS sends multiple smaller packages, BXL tries to send as big packages as possible. Big in this instance is up to 65536 bytes, and BXL creates a new package when the size of rows and columns has reached 65536.

From a code perspective we realized that the sqlmin!CQScanUdx::PushNextChildRow routine was where everything happened (or in sub routines). We were aware of that routine from

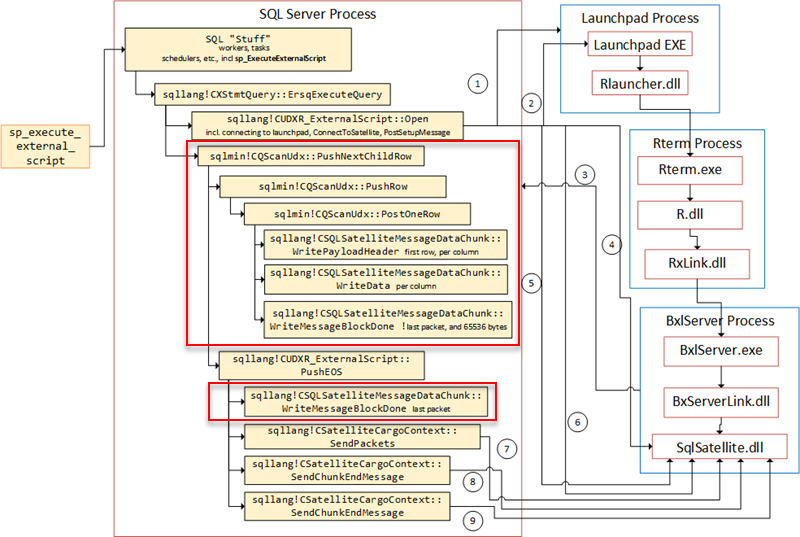

Internals - XII, where we looked at what sent the TCP packets to the SqlSatallite. Now we saw how PushNextChildRow calls PushRow which calls WritePayloadHeader if it is the first row and WriteData. If it is a packet that has reached the size of 65536 and there are more packets, WriteMessageBlockDone is called. Then, if it is the last packet, PushEOS is called and PushEOS calls WriteMessageBlockDone. The figure below illustrates the flow:

Figure 7: BXL Code Flow

I you believe you have seen Figure 7 before or that it looks similar to some other figure, it is because is is a copy of a figure in Internals - XII. Here I have compressed some routines in order to fit in the ones we learned about today. The numbered arrows in Figure 7 shows the communication out from SQL Server, and in what order it happens:

- SQL Server opens named pipe connection to the launchpad service.

- Message sent to the launchpad service.

- After the call above, the SqlSatellite opens a TCP/IP connection to SQL Server.

- SQL Server sends the first packet to the SQL Satellite for authentication purposes.

- A second authentication packet is sent to SqlSatellite.

- The script is sent from inside

sqllang!CSatelliteProxy::PostSetupMessage - The data for

@input_data_1is sent. - The first end packet is sent.

- The second end packet is sent.

What the figure above illustrates can also be expressed in pseudo-code like so:

|

|

Code Snippet 11: Pseudo Code Flow for Writing BXL Packets

I do believe this was the last post about BXL, *unless I can find out why nullable columns causes these big, big packets, that we have discussed in quite few posts. Most recently in Internals - XIV.

~ Finally

If you have comments, questions etc., please comment on this post or ping me.

comments powered by Disqus