A little while ago I wrote a blog post, Java & SQL Server 2019 Extensibility Framework: The Sequel, about changes in SQL Server 2019 CTP 2.5 impacting how we write Java code for use from SQL Server. While I wrote that post, Microsoft released SQL Server 2019 CTP 3.0, and, (surprise, surprise), that release contains more changes affecting Java code in SQL Server.

This post covers those changes as well as discusses what SQL Server Extensibility Framework and Language Extensions are.

Before we “dive” into the “nitty-gritty” let look at the data we use in this post.

Demo Data

The data we see here is for you who want to “code along”. It is lifted from the post mentioned above:

|

|

Code Snippet 1: Create Database

We see from Code Snippet 1 how we create a database where we want to run some Java code from.

Background

In SQL Server 2016, Microsoft introduced SQL Server R Services. That allowed you to, from inside SQL Server, call to the R engine via a special procedure, sp_execute_external_script, and execute R scripts. The R engine was, (and is), part of the SQL server installation but it runs as an external process, (not in SQL Server’s process), and subsequently, R is seen as an external language.

In SQL Server 2017, Microsoft added Python as an external language and renamed SQL Server R Services to SQL Server Machine Learning Services. The way Python works in SQL Server is the same as R:

- The Python engine is included in the SQL Server installation.

- You execute Python code using the

sp_execute_external_script. - Python runs in an external process.

The communication between SQL Server and the external engine goes over the Launchpad service:

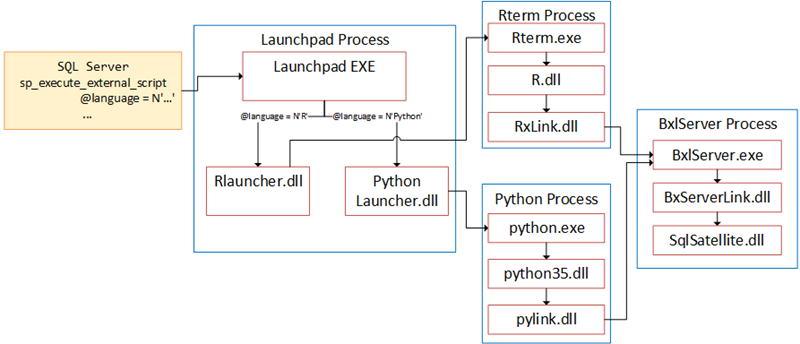

Figure 1: External Script and Language

We see in Figure 1 how:

- We execute the procedure

sp_execute_external_script. - That calls into the Launchpad service.

- The Launchpad service passes the script into the relevant launcher based on the

@languageparameter insp_execute_external_script. The knowledge of what launcher to call lives inside of the Launchpad service. - The launcher dll loads the relevant external engine, passes the script to the engine and executes.

The above is a very high-level overview of how it works, and you can read more about the inner workings of it in SQL Server R Services.

So, a launcher dll is a piece of code, typically written in C++, who knows how to interact with the external engine.

After the introduction of Python in SQL Server 2017, the documentation started to mention how R and Python code runs in an extensibility framework, which is isolated from the core engine processes. Around this time, Microsoft started to mention the possibility of other languages becoming part of the extensibility framework.

SQL Server 2019 & Java

At the time of SQL Server 2017 and the inclusion of Python, the extensibility framework was more just a name or - at least - it was purely some internal Microsoft SQL Server code. It was nothing that you and I could use directly. Then came SQL Server 2019.

In CTP 2.0 of SQL Server 2019, Microsoft made Java publicly available as an external language. Having Java as an external language may not seem that much different from R/Python, but there are some differences:

- Java is a compiled language, where we call into a specific method. R/Python are scripting languages where we send a script to the engine.

- R/Python are part of the SQL Server install, together with launcher dll’s and so forth. For Java, there is an equivalent of a launcher dll, (

javaextension.dll), which calls into the JVM. The difference here between R/Python and Java is that the JVM is not part of the SQL Server install but must be installed separately.

What Microsoft could have done with the Java integration in SQL Server 2019 was to just treat it as R/Python, and “hardcode” Java as a language in the Launchpad service and let the Launchpad service call the javaextension.dll.

NOTE: There are most likely quite substantial differences between the

javaextension.dlland the R/Python launcher dll’s, but in his post, I treat them as being more or less equivalent.

However, Microsoft did not “hack” the Launchpad service, but what they did was, with the view to “properly” expose an extensibility framework with multiple external languages, that they introduced some new components (hosts). The Launchpad service calls these hosts for all languages except R/Python. Yes, yes, I do know that for now (we are now at CTP 3.0), it is only Java, but…

NOTE: In future posts I will talk more about these new components.

Having read this far in the post you may say: Hey Niels, this is all interesting and all, but you have not said anything we don’t already know.

External Language

Ok, so let us see what this is all about. Remember how we, in the

Java & SQL Server 2019 Extensibility Framework: The Sequel post, discussed how SQL Server CTP 2.5 introduced a Java SDK, mssql-java-lang-extension.jar, that we as developers need to develop against when we write Java code we want to execute from SQL Server. That is a requirement in CTP 3.0 as well, but the way you get the .jar file is different. In CTP 2.5 you downloaded the file, whereas in CTP 3.0 the file is part of the SQL Server distribution, and you find it at: ..\<path_to_sql_instance>\MSSQL\Binn\mssql-java-lang-extension.jar.

NOTE: The file name of the SDK is somewhat misleading as it is not the Java language extension itself, it is the SDK for the Java language extension.

We know from the

post mentioned above that we need to create an external library based on the .jar file, so I copy the file to a more accessible location and then:

|

|

Code Snippet 2: Create External SDK Library

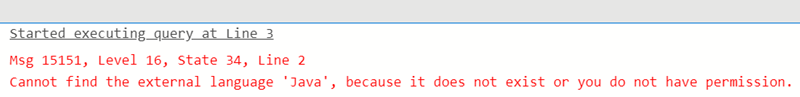

In CTP 2.5 the code in Code Snippet 2 runs just fine, but when we run it in CTP 3.0 we get an exception:

Figure 2: Exception when Creating External Library

The exception we see in Figure 2 is due to one of the changes in CTP 3.0: an external language needs to be “registered” with SQL Server before we can reference it. Registering a language with SQL Server allows Microsoft and/or 3rd parties to expose arbitrary languages to be used from SQL Server.

What we register is the actual language extension file for that particular language, together with a name for the language.

Create External Language

The way we register/create an external language is similar to how we create an external library; we use a CREATE EXTERNAL ... DDL statement: CREATE EXTERNAL LANGUAGE:

|

|

Code Snippet 3: Signature CREATE EXTERNAL LIBARY

The arguments we see in Code Snippet 3 are:

language_name: A unique name for the language.owner_name: This optional parameter specifies the name of the user or role that owns the language.file_spec: Thefile_specspecifies the content of the language extension file for a specific platform, and it can either be in the form of a file location (local path/network path) or a hex literal. If we install the package from a file location, the file needs to be in the form of an archive file (zip on Windows,tar.gz` on Linux).file_name: Name of the language extensiondllorsofile.platform: ThePLATFORMparameter, which defines the platform for the content of the library. ThePLATFORMcan be Windows or Linux, and it defaults to Windows.parameters: Optional parameters for the external language runtime. Not supported in CTP 3.0.env_variables: Optional parameter to set environment variables for the external language runtime. Not supported in CTP 3.0.

The above is a somewhat simplified explanation of the arguments, but it should be enough for us to get started. You find a more in-depth description here.

Using CREATE EXTERNAL LANGUAGE

Before we write code to create an external language, let us think back to what I wrote in

SQL Server 2019, Java & External Libraries - I, and

Installing R Packages in SQL Server Machine Learning Services - III about CREATE EXTERNAL LIBRARY and how there were some new system catalog views introduced together with CREATE EXTERNAL LIBRARY: more specifically sys.external_libraries and friends. The same is true for CREATE EXTERNAL LANGUAGE:

sys.external_languages- contains a row for each external language in the database.sys.external_language_files- contains a row for each external language extension file in the database.

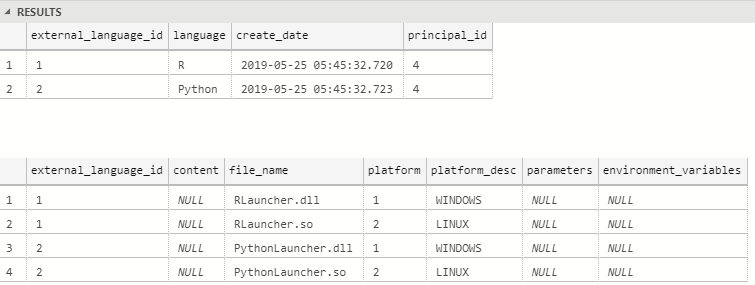

Let us look at what we see if we run a SELECT against those two catalog views. I do this on a freshly installed CTP 3.0 where I have not created any external languages. I have only enabled Machine Learning Services together with R and Python. When I execute my SELECT’s, I see:

Figure 3: External Languages

What I see in Figure 3 surprises me somewhat; even though I have not created any external languages myself, the mere fact that I have enabled Machine Learning Services bootstraps two languages: R and Python, as we see in the upper result grid, (SELECT * FROM sys.external_languages). Notice also how in the lower result grid, (SELECT * FROM sys.external_language_files), I see files for both the Windows as well as the Linux platforms.

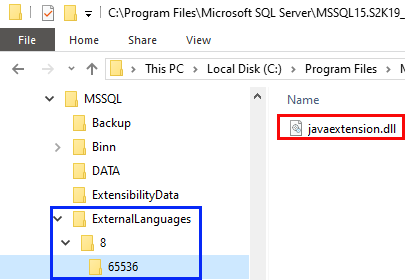

So let us create Java as an external language. We know from above that the Java language extension file is the javaextension.dll, which is part of the SQL Server distribution and you find it in the same directory as the SDK .jar mentioned above: ..\<path_to_sql_instance>\MSSQL\Binn\javaextension.dll. However, you cannot use it directly in the CREATE EXTERNAL LIBRARY call; you need to archive it into a .zip file first - as mentioned above.

I zipped the dll and placed it in the same location as the .jar file in Code Snippet 2 and I am now ready to create the external language:

|

|

Code Snippet 4: Creating External Language

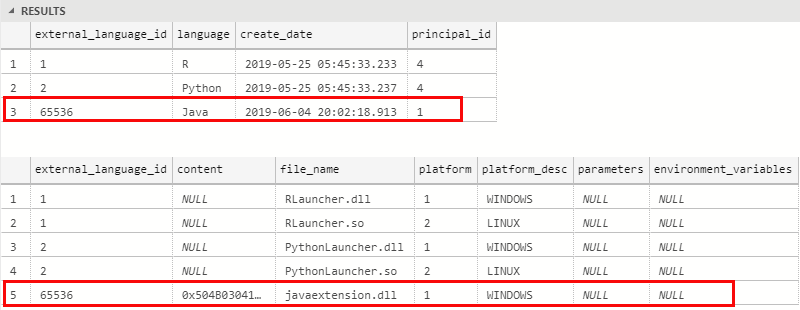

The reason we, in Code Snippet 4, set the file name in the FILE_NAME parameter is that the zip file may contain multiple files and the file name defines the language extension. After we execute the code in Code Snippet 4, we run the SELECT statements we used above against the external language catalog views, and we get:

Figure 4: Java External Language

WWe see in Figure 4 how we have added Java as an external language to the JavaTestDB database. In the lower result grid, we see how the binary representation of the zip file is persisted as well, the same as it is for external libraries. Speaking of external libraries, in the posts I did about those, we discussed how the external libraries, when resolved, were copied to file directories: ..\<path_to_sql_instance>\MSSQL\ExternalLibraries. I wonder if it is the same for external languages?

Sure enough, when looking at ..\<path_to_sql_instance>\MSSQL I see an ExternalLanguages directory, and as with external libraries, it is empty. Remember from the posts mentioned above, how the ExternalLibraries directory got populated when we resolved an external library. Let us see if it is the same for external languages.

As we have created the external language, we can now do what we tried to do earlier; create the external SDK library. So, we run the code in Code Snippet 2 again, and now it succeeds. We verify that by executing: SELECT * FROM sys.external_libraries. When we have deployed the SDK, we can deploy our Java code that we want to call from inside SQL Server. In this post, I use the same Java code as in the first example in

Java & SQL Server 2019 Extensibility Framework: The Sequel:

|

|

Code Snippet 5: JavaTest1 Class and Execute Method

I compile the code in Code Snippet 5 into a .jar file which I then deploy:

|

|

Code Snippet 6: Deploy Java Code

We see after we ran the code in Code Snippet 6 that nothing changed in the ExternalLanguage directory, and nothing changed for that matter in ExternalLibraries either. Hopefully, we see some changes when we execute the code calling into our class:

|

|

Code Snippet 7: Execute Java Code

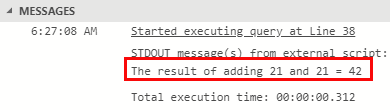

The result after running the code in Code Snippet 7:

Figure 5: Success

As we see in Figure 5, the code we ran in Code Snippet 7 executed successfully. So, what has happened in the file system:

Figure 6: File System External Languages

In Figure 6 we see how, when executing the code in Code Snippet 7, the language extension file gets copied to a directory with the structure ExternalLanguage | Database Id | External Language Id | File Name. As with external libraries, SQL Server loads the extension from that directory.

What is interesting is that even though R/Python shows as external languages in the catalog views, when you execute some R/Python code, the launcher dll’s do not get copied to the external languages directory.

Summary

In this post, we discussed the requirement in SQL Server CTP 3.0 to register any external language other than R/Python which you want to use from inside SQL Server.

NOTE: At the time of writing this post the only external language besides R/Python is Java, but other languages will most definitely become available.

So, what did we say:

- Before you can use Java as an external language, you need to register it with SQL Server in the database you want to call Java code from.

- You register not only the language name but also the language extension: the bridge between SQL Server and the external runtime.

- To register you call

CREATE EXTERNAL LANGUAGE, where you can either use a file path or a binary representation of the archive file containing the language extension. - In future releases you can send in parameters as well as environment variables in the

CREATE EXTERNAL LANGUAGEcall.

Something we didn’t touch upon in this post was that the security model for executing against an external language has changed somewhat. We cover that in a future post.

~ Finally

If you have comments, questions etc., please comment on this post or ping me.

comments powered by Disqus