Way back when (in 2010 as a matter of fact), I wrote a couple of blog-posts ( here and here) about error handling in the new CTP releases of SQL Server Denali. Denali was what would become SQL Server 2012.

The new functionality built upon what was introduced in SQL Server 2005 - the notion of structured exception handling through BEGIN TRY END TRY followed by BEGIN CATCH END CATCH. In those blog-posts I was fairly positive, and saw the new functionality as something useful and very well worth implementing. I am still positive, however since then I have used the new functionality introduced in SQL Server 2005 extensively in production and have come across some gotchas that I thought would be worth writing a blog-post about.

Background

Before SQL Server 2005 was introduced, and with that structured exception handling as mentioned above, the way we handled error conditions in SQL Server was to write something like so:

|

|

Code Snippet 1: Old Style Error Handling

In your stored procedures, you had to insert code like above after each statement where you wanted to check for errors. Part of the error-handling code quite often would be some logging/auditing and general rewind/cleanup. Typically you would also re-raise the error so that calling procs would be made aware that something has happened, and in the calling procs you would have similar logic to catch the errors being raised.

All in all, quite a lot of code to write. At Derivco we have a lot of stored procedures, and they can be fairly big (3000 - 4000 loc), so you can imagine the number of error checks we have in them.

TRY CATCH

Writing the above mentioned error-handling code feels quite arcane if you compare what you would do in other programming languages. So in SQL Server 2005 Microsoft introduced the notion of structured exception handling as I mentioned above, and it was implemented through BEGIN TRY ... END TRY and BEGIN CATCH ... END CATCH blocks. As with other programming languages you can have one or more TRY … CATCH blocks, and when an error happens inside the TRY block, the code in the CATCH block is immediately hit.

|

|

Code Snippet 2: Error Handling with TRY … CATCH

When the BEGIN TRY ... END TRY block together with BEGIN CATCH ... END CATCH executes, it creates a special error context, so that any errors happening will be caught by the closest CATCH block. In other words, errors “bubble” up to the closest CATCH block, within the same SPID. Keep this in mind, as it is important when we discuss some of the “gotcha’s”.

THROW

Ad good as the new error-handling functionality was in SQL Server 2005, there were still some pieces missing when comparing t-sql with other languages error-handling. One big glaring missing piece was how to re-throw a caught exception. What you typically would do if you wanted to re-throw was to capture the error text, either from sys.messages pre SQL Server 2005, or from ERROR_MESSAGE() in SQL SERVER 2005+, and in both cases then use the captured text in RAISERROR.

Note about RAISERROR:

- It allows you to throw an error based on either an error number or a message, and you can define the severity level and state of that error.

- If you call

RAISERRORwith an error number, that error number has to exist in sys.messages. - You can use error numbers between 13001 and 2147483647 (it cannot be 50000) with

RAISERROR.

RAISERROR has been around “forever”, and for SQL Server 2012 Microsoft introduced THROW as new function to be used when raising exceptions. Some of the features of THROW:

THROWcan be used to re-throw an exception.- Using

THROWyou can throw a specific error number together with an accompanying message.

Code snippet 3 below shows an example of this:

|

|

Code Snippet 3: Error Handling with THROW and TRY … CATCH

If you have managed to stay awake until now, you probably wonder where is the problem with all this, this looks pretty sweet, or as we use to say in the team I work for in Derivco; “What could possibly go wrong?”! Whenever we say that, it seems that quite a few things can go wrong :) and the same thing holds true here, as we will see!

The Problem

The problem comes in when you are mixing “old” (pre 2005), with “new” (2005+) error handling. You may ask: “why would you ever want to do that, why not use only the new cool features?”. In fact that’s what I asked when I visited Derivco back in 2009 and taught a Developmentor SQL Server course for the team I eventually would work for. Boy was that a stupid question!

The answer - in Derivco’s’ case - is complexity. In our main OLTP production database we now have ~5,000 stored procedures, and the call stacks can nest 10 - 15 procedures deep. In addition, our procedures are not simple CRUD, but we do have LOADS of business logic in them. So you cherry-pick what procs to edit, most likely some you are changing anyway, and all new procs are written using the new error-handling. What could possibly go wrong with this approach?!

Well, chances are that the new/edited procs are part of a call chain, and not necessarily the last proc in the chain. This is now the situation where issues can happen. Let’s look at this a bit closer. In the demo code for this post, we have initially four procedures:

dbo.pr_Callerwhich calls intodbo.pr_1which calls intodbo.pr_2which calls intodbo.pr_3which is the last proc in the chain.

The three first procs pr_Caller, pr_1 and pr_2 looks almost identical, and I let dbo.pr_Caller be the “showcase”:

|

|

Code Snippet 4: Example of Calling Proc

The last proc in the chain - dbo.pr_3 - is somewhat different in that it generates an error:

|

|

Code Snippet 5: Error Proc

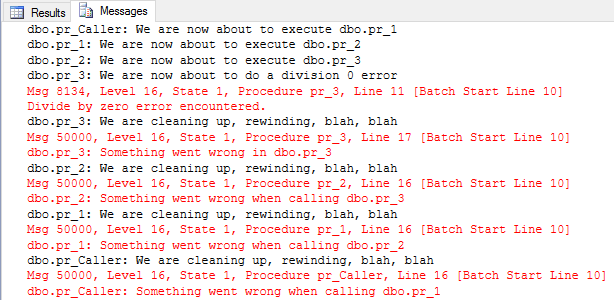

When you look at the procs you can see that they all use the old style error handling, and are doing clean-ups etc in the IF(@err <> 0) block. If you execute the calling proc: EXEC dbo.pr_Caller, the result in the Message tab in SQL Server Management Studio (SSMS) would look something like:

Figure 1: Output from Error Procs

From the figure above we can see:

- we are calling into each proc: We are now about to execute.

- the division by 0 error happens: Divide by zero error encountered.

- each proc in the call chain cleaning up, etc.: We are cleaning up ….

This is good (well not good that we are getting an error), but we are handling it and cleaning up after ourselves. We may perhaps write the errors to some logging tables, so that we in case of un-expected behavior can trace and see what has happened.

Let us now assume that we need to change dbo.pr_1, to add some new functionality, whatever. This is now a good time to alter this old proc to use the new “cool” error-handling:

|

|

Code Snippet 6: Edited Proc

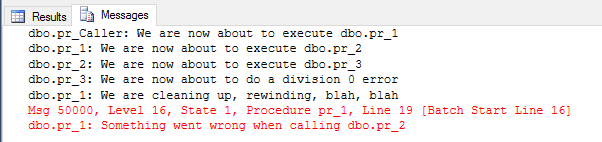

No problem with the changes, however when you execute you get following result:

Figure 2: Output from Altered Error Procs

Where is the cleanup in dbo.pr_2 and dbo.pr_3, as an error clearly has happened as something was caught in dbo.pr_1? Oh, and what happened with the error-handling in dbo.pr_Caller, we did raise an error in dbo.pr_1?

The last question is the easiest to answer, and fix; if you want old style error-handling to be able to catch an error raised from within a CATCH block, the RAISERROR MUST be followed by a RETURN, and it has to be a RETURN with no variables! So change the CATCH block in dbo.pr_1 to:

|

|

Code Snippet 7: Use RETURN After Raising an Exception

If you after the above change were to EXEC dbo.pr_Caller you would see how pr_Caller would handle the error raised in pr_1 as well. The first issue which arguably is more severe is easy to answer; it has to do with that “error context” mentioned in the beginning.

Error Context (a.k.a “Go Straight to CATCH Without Passing IF(@@ERROR”)

As I mentioned in the beginning, when a stored procedure is executed, and during the execution it comes across BEGIN TRY block(s), a special execution context(s) is created from the point of the first BEGIN TRY . This context “wraps” all code from that point on, and ensures that if an error happens, the execution will stop and the closest BEGIN CATCH block will be hit. That is the reason why the cleanup code in neither dbo.pr_3 nor dbo.pr_2 was executed.

The answer was easy, but the fix is neither easy nor straightforward. The only way (I am aware of) is that if you edit/create a new proc using the new way of handling errors, you need to ensure that the whole call-stack from that way onward is also using the new way.

THROW

Finally (pun intended), let’s discuss THROW, as so far we have not seen any traces of it in the code. Let us edit dbo.pr_3 to use new error handling as well as using THROW to re-throw an exception:

|

|

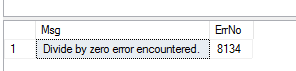

At the same time in the error handling code of dbo_pr1, let’s select out the error message as well as error number, right before we raise the exception: SELECT ERROR_MESSAGE() AS Msg, ERROR_NUMBER() AS ErrNo, and then EXEC dbo.pr_Caller. All should be as before, and in the Results tab in SSMS you should see:

Figure 3: Correct Error Number and Message

By receiving 8134 as error number we can see that THROW actually does what it is supposed to. However what happens if we were to edit dbo.pr_1 to also THROW, seeing that dbo.pr_Caller is still doing old style error handling:

|

|

Execute the pr_Caller, and notice the output: there is nothing there from dbo.pr_Caller. If THROW is used down in the call chain somewhere, there has to be a calling proc using the new error handling!

Summary

So in summary:

- TRY CATCH blocks ARE good!

- However, be careful when mixing new TRY CATCH with “old” @@ERROR

- You need to ensure all nested procedures called inside the TRY block is also using TRY CATCH.

- If raising an error in a CATCH block, ALWAYS follow the RAISERROR with a RETURN (no value).

- Unless you can guarantee that your code will always use TRY CATCH, stay away from THROW.

Download the demo code from here!!

comments powered by Disqus