This is the eleventh post in a series about Microsoft SQL Server R Services, and the tenth post that drills down into the internal of how it works. To see other posts (including this) in the series, go to SQL Server R Services.

In Internals - IX I said we were nearing the end of the internals part is this series, and I had planned this post to be the final post in the Internals part. However while investigating how data is sent between SQL Server and the external components I realized that I would need to probably do two more posts (apart from this) for Internals.

Anyway, in this post we’ll see how data is sent to the R components from SQL Server.

The “cool” thing by writing all these Internals posts is that as we go along, I learn more things about how it works. For example when I wrote the Internals - I, I was quite confident in how things worked. Today, how I thought it might have worked, is not entirely correct (as we’ll see). So, as I said I have learned a lot along the way.

Recap

Since I thought this would be the last Internals post I wanted to do a full recap what has been covered so far. We now know that this is not the last Internals post, but since I have done the work, lets do the full recap anyway even though there will be one or two more posts covering Internals. Since I am lazy, I shamelessly “steal” the recap from Internals - VIII and add what we’ve done since then.

The first post in the series -

Microsoft SQL Server 2016 R Services Installation - covered the installation of SQL Server 2016 R Services, and it also touched upon the external procedure which allows us to execute external scripts; sp_execute_external_script. We looked at the signature of the procedure as well as executing the equivalent to a “Hello World” script.

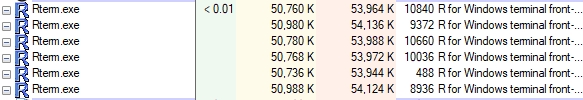

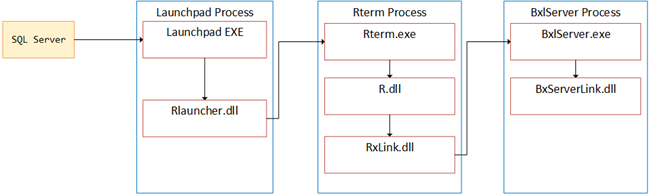

In the subsequent posts we talked about - when executing sp_execute_external_script - how SQL Server calls into the launchpad service, and how the launchpad service - through the rlauncher.dll creates multiple Rterm.exe processes as in Figure 1 below. One of the processes will be used to run the external script:

Figure 1: Rterm.exe Processes

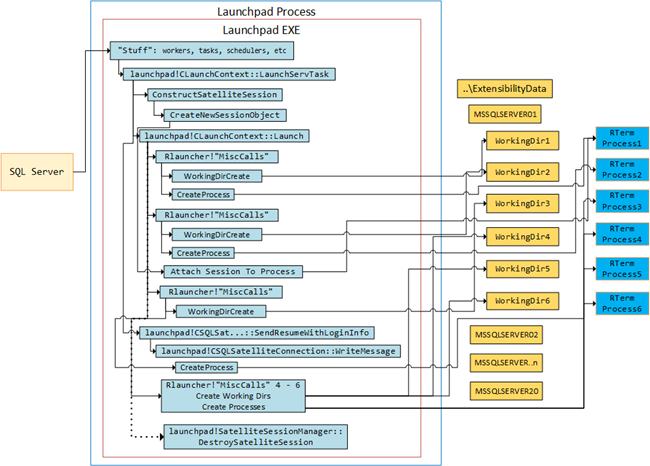

I addition to creating Rterm.exe processes, the launchpad service also creates backing directories for those processes. These backing directories are used for saving output, intermediate results etc. The following figure was used to illustrate what the call flow looks like:

Figure 2: Call Flow Executing sp_execute_external_script

We discussed how the number of processes can be controlled by the PROCESS_POOL_SQLSATELLITE_GROWTH setting in rlauncher.config file, and how it defaults to 5 if nothing is set.

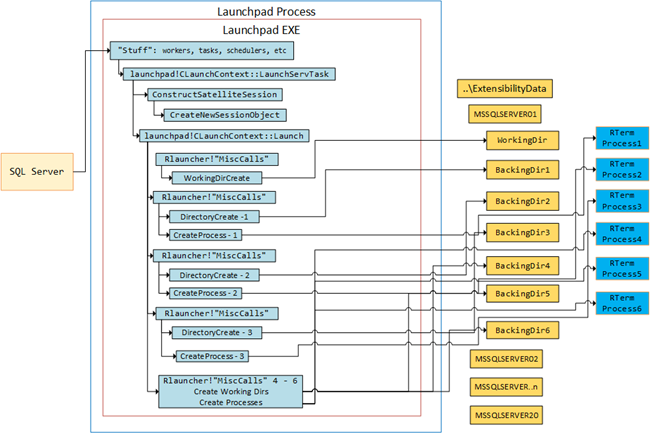

In Internals - VI we came back to the backing directories, and we realized that in addition to the backing directories created for the Rterm processes, one more directory is created. This directory will be the “official” working directory for the session, and we showed this using this figure:

Figure 3: Launchpad, Directories and Processes

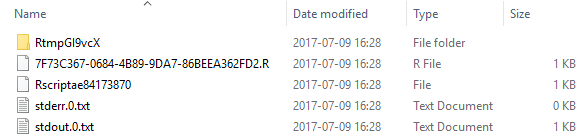

While we were investigating the directories created in Internals - VI, we saw that - while we executed an external script, files and sub-directories were created in the various backing directories:

Figure 4: Contents Process Directory

In Figure 4 we see the content of the directory which is the processing directory, and in

Internals - VII we looked into what creates those files/directories and what they are for. We came to the conclusion that both the launchpad service (probably through the rlauncher.dll) created some files, whereas Rterm.exe created others.

So far in the series we have covered what happens up until the Rterm process is created. In

Internals - VIII we saw how Rterm.exe was the entry point into R and how Rterm loaded the R.dll and RxLink.dll. RxLink acts as a conduit between the open source R and Microsoft’s BxlServer.exe. BxlServer is the executable hosting RevoScaleR, and it also coordinates with the R runtime in order to manage exchanges of data with SQL Server. To help with data exchanges with SQL Server, BxlServer loads BxServerLink.dll, who does a lot of data conversions etc. We illustrated all this with following figure:

Figure 5: BxlServer

In

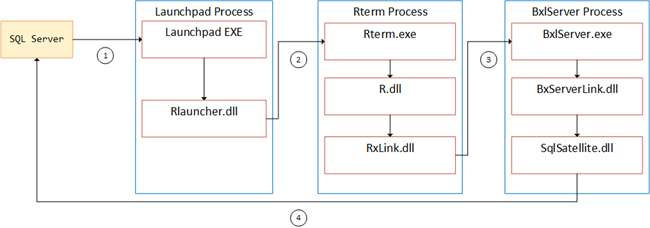

Internals - IX we tried to determine what communication mechanisms are used between the various components, and what components are involved to return data to SQL Server. We saw that in addition to BxlServer and BxServerLink we also had SqlSatellite.dll. SqlSatellite is an API to support external code and external run times, and it is the dll that BxlServer relies on in order to exchange data with SQL Server.

We eventually figured out how communication takes place between the various components and we used the figure below to illustrate the comms mechanisms:

Figure 6: How Communication Happens

So in Figure 6 we see a high level view of the architecture, and the numbers denotes the comm mechanisms:

- 1 - named pipe.

- 2 - IOCP.

- 3 - named pipe.

- 4 - TCP/IP

By now we have a certain understanding how it works, and we do know that the SqlSatellite communicates with SQL Server. I this post we’ll look a little bit deeper into what is happening.

Demo Code

As in quite a few of the other posts, let’s have a look at the demo code we’ll be using. In this post we’ll re-use what we had in Internals - IX. First the code to setup the database, and a table with some data:

|

|

Code Snippet 1: Setup of Database, Table and Data

The code we’ll use to execute:

|

|

Code Snippet 2: Code to Execute

Even though the code in Code Snippet 2 doesn’t do very much, it serves it’s purposes for what we want to do. Notice that we can pause the execution thought the commented out Sys.sleep statement, if we want to examine what is happening.

Data Transfer/Exchange

We know by now (at least after

Internals - IX) that the SqlSatellite has something to do with data exchange. In addition we also know that the launchpad service (in reality rlauncher.dll) talks to R, and can potentially transfer data. So the question is who transfers data, and what data is transferred by who? If you look at the code in Code Snippet 2, there are various data transfers happening:

- The R script is sent to R.

- A dataset is sent in to R trough the

@input_data_1parameter. - Variables (

pidandd) are printed through thecatstatement. - A dataset is returned from the

OutputDataSetvariable. The schema of the resultset is defined inWITH RESULT SETS ....

In addition to the scenarios above, parameters are also transferred (both in and out), but for now we’ll leave those out of the discussion.

So, cast you mind back to

Internals - I and

Internals - II (“woooosh” - that’s the sound of your mind being cast back), where we discussed what happens when we execute sp_execute_external_script. We said that, SQL Server’s sqllang!SpExecuteExternalScript is called, and SQL Server then opens a named pipe connection to the launchpad service and sends a data packet to the service. The launchpad service creates the necessary processes (RTerm) etc., and sends the data packet it received on tho the executing process. The assumption made, at least implicitly, was that all the necessary data is transferred to the R engine via the packets SQL Server sends to the launchpad service and that the launchpad sends it on. For return data the assumption was that the data is returned the same way. That’s what I thought up until

Internals - IX when we discussed the SqlSatellite. So, let’s see what really happens.

Data -> R

To see how data is sent to R, let’s fire up our trusted WinDbg an attach it to both the SQL Server process as well as the launchpad process:

- Restart SQL Server and the launchpad service (just to start afresh).

- Attach WinDbg (as admin) to the two processes (one WinDbg instance each).

Now we can set some break-points for both SQL Server as well as the launchpad process, and the break-points we set are some of the ones we have used in previous posts:

- SQL Server:

sqllang!SpExecuteExternalScript - SQL Server:

sqllang!CSQLSatelliteConnection::OpenNpConnection - SQL Server:

sqllang!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessage - SQL Server:

sqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript::ConnectToSatellite - Launchpad:

launchpad!Np::AcceptConnection - Launchpad:

launchpad!Np::ReadAsync - Launchpad:

launchpad!CSQLSatelliteCommunication::SendResumeWithLoginInfo - Launchpad:

launchpad!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessage

The code we’ll use initially is not what we see in Code Snippet 2, but something very, very basic:

|

|

Code Snippet 3: Basic External Script

The reason for using simple code like in Code Snippet 3, is that it might make it easier to understand what is happening, and we can compare with what is happening when executing some other, not so basic, code. Notice how in Code Snippet 3 there is a Sys.sleep. It is there to make it easier to determine - when debugging - when data is sent to R and when data is coming back.

We can now go ahead and execute the code in Code Snippet 3, and what we will see is how we break in following order:

sqllang!SpExecuteExternalScriptis called.sqllang!CSQLSatelliteConnection::OpenNpConnectionlaunchpad!Np::AcceptConnectionlaunchpad!Np::ReadAsynclaunchpad!Np::ReadAsynclaunchpad!Np::ReadAsyncsqllang!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessagelaunchpad!Np::ReadAsynclaunchpad!CSQLSatelliteCommunication::SendResumeWithLoginInfolaunchpad!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessage- notice how nothing happens in the SQL process untilWriteMessageis executed.sqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript::ConnectToSatellitesqllang!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessagesqllang!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessage- Pause for

Sys.sleep sqllang!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessagesqllang!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessagelaunchpad!Np::ReadAsynclaunchpad!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessage

For now we won’t bother over what happens after the Sys.sleep, but we can see some behaviors that might make us doubt that we have been entirely correct in our previous assumptions how data is sent to the R engine. I am thinking about some of the sqllang!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessage who doesn’t have a corresponding launchpad action.

Let us see what happens if we were to execute the code in Code Snippet 2. Before you execute the code, change the SELECT y ... statement to be SELECT TOP(10) y .... When you execute you will see a third sqllang!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessage before the Sys.sleep. After the Sys.sleep there’d be a third sqllang!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessage and a second launchpad!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessage. What happens if the TOP clause was changed to be TOP(100000) (hundred thousand)? Then there’d be 5 sqllang!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessage after ConnectToSatellite and the rest would stay the same. Based on this, there seems to be some impact based on how much data is being transferred, and it seems that the launchpad service is bypassed for at least some data transfer (as we don’t see any extra launchpad!Np::ReadAsync).

So if the launchpad service is being bypassed, what would be used to transfer data? Seeing that we discussed SqlSatellite in

Internals - IX, and also mentioned SqlSatellite above, that might be the answer. Unfortunately we have no debug symbols for SqlSatellite or its host BxlServer.exe, so we cannot use WinDbg to check and see if we are correct. What we’ll do instead is to take advantage of the fact that SqlSatellite communicates with SQL Server using sockets, and we’ll use

Process Monitor, to see if we can find any interesting things.

NOTE: We used Process Monitor in Internals - VII, so go back there if you need pointers of how to use Process Monitor.

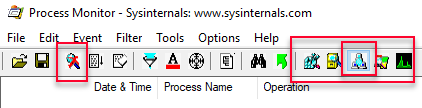

After you have started up Process Monitor as admin, suppress any event monitoring to start with, as not too be flooded with events. You should also just choose to see event types you are interested in, in this case “Network Activity”. You can do this through the icons in the tool bar, as per below:

Figure 7: Communication Mechanisms

In Figure 7 we see how event capturing is paused due to having clicked on the magnifying glass (in the first outlined box). We also have chosen to receive only “Network Activity” events (the second outlined box). You can see that “Network Activity” is enabled as it has a barely visible light-blue background, and the others do not. Having set this up, now is a good time to clear out any events that might have been captured, so under the Edit menu click Clear Display.

So what are we going to use Process Monitor for? Well, as I mentioned above, there is socket communication between SQL Server and SqlSatellite, so we’ll try and capture that particular traffic. In order to do this, we’ll set up some Process Monitor event filters, the same way as we did in

Internals - VII. The filters we’ll setup are for “Process Name” and “Operation”. The process we initially are interested in is BxlServer.exe, since BxlServer hosts the SqlSatellite. The operations we want are “TCP Connect” and “TCP Receive”. The idea is that we will be able to see when a connection is made between SQL Server and the SqlSatellite and if there is any data sent to the satellite from SQL Server.

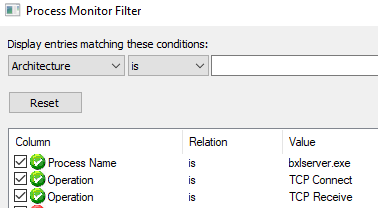

To set the filter; under the Filter menu click the Filter menu item, and the “Process Monitor Filter” dialog will be shown. To create the filter we enter the conditions we want to match:

- The Process Name (from first drop down) should be is (from second drop down):

bxlserver.exe. - Operation (first drop down) is (second drop down): “TCP Connect”

- Operation (first drop down) is (second drop down): “TCP Receive”

The conditions should be included and added, and when you are done the filter dialog should look something like so:

Figure 8: Filters BxlServer

What the filter says is that any “TCP Connect”, or “TCP Receive” events for bxlserver.exe should be monitored and displayed. Oh, and the only three filter criteria active (green check-mark) should be the top three ones. When you have clicked “OK” out of the dialog box, we are ready to test this out:

- Ensure that you still are attached with the two WinDbg instances to SQL Server and the launchpad processes.

- It my be a good idea to in WinDbg clean out the command window (

.cls).

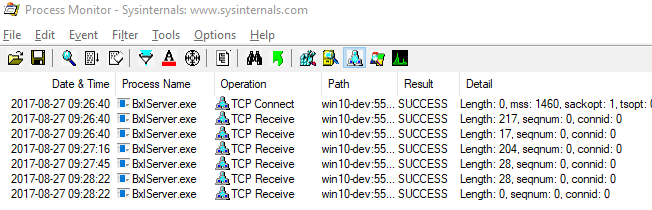

For this test we’ll use the code in Code Snippet 3, just so we can get something of a baseline. When you execute the code, look at what is happening in the two WinDbg instances as well as in Process Monitor. The flow of the events are something like this:

sqllang!SpExecuteExternalScriptis called.sqllang!CSQLSatelliteConnection::OpenNpConnectionlaunchpad!Np::AcceptConnectionlaunchpad!Np::ReadAsynclaunchpad!Np::ReadAsynclaunchpad!Np::ReadAsyncsqllang!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessagelaunchpad!Np::ReadAsync- TCP Connect

- TCP Receive

- TCP Receive

launchpad!CSQLSatelliteCommunication::SendResumeWithLoginInfolaunchpad!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessagesqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript::ConnectToSatellitesqllang!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessage- TCP Receive

sqllang!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessage- TCP Receive

- Pause for

Sys.sleep sqllang!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessage- TCP Receive

- TCP Receive

sqllang!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessagelaunchpad!Np::ReadAsynclaunchpad!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessage

The output in Process Monitor looks like so (I have truncated the Path and Detail columns somewhat):

Figure 9: Process Monitor Base Output

From what we can see, the three first TCP events happens while we connect. The fourth happens after a WriteMessage, and the fifth after the second WriteMessage before Sys.sleep. The remainders we don’t care about right now, as we’ll look at them when we investigate how data is returned to SQL Server. At this stage we cannot say for sure what happens, and what the different packages are for - but we can definitely see that data is being sent to SqlSatellite from SQL Server.

OK, so let’s try with some other code:

|

|

Code Snippet 4: Longer R Script

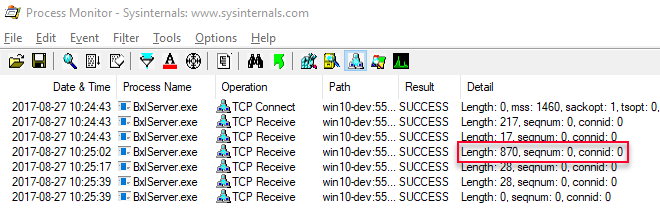

There is not much difference between what we execute in Code Snippet 3 and this code in Code Snippet 4, except for the Code Snippet 4 script being longer. Will size matter; let’s look at what happens in WinDbg and the output from Process Monitor after we have executed the code in Code Snippet 4:

Figure 10: Process Monitor Output Longer Script

The flow in WinDbg did not change at all, and the same amount of packages were sent. However, the fourth event (packet), following sqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript::ConnectToSatellite and sqllang!CSQLSatelliteConnection::WriteMessage has a different size (870 vs. 204), as can be seen in Figure 10. Hmm, this would certainly indicate that the script to execute is sent over the socket connection to SqlSatellite, and not via the named pipe connection to the launchpad service. What about data going to the R engine? Based on what we saw when we executed the code in Code Snippet 2 with a SELECT TOP(100000) y ... (multiple WriteMessage calls) we can probably safely assume that the data is also sent over the TCP connection. Just to ensure this really is the case we can test it out. We’ll change the code slightly, once again to have something to compare it to:

|

|

Code Snippet 5: External Script with Data Select

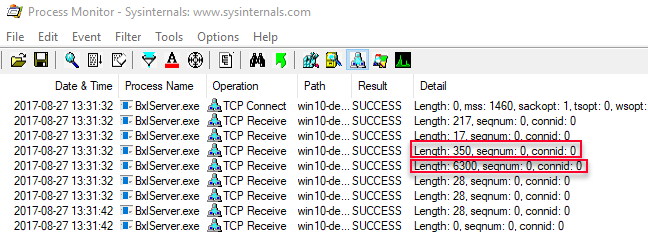

The output from Process Monitor looks as follows:

Figure 11: Process Monitor Output Data Select

This is strange, the R script we executed here is exactly the same as in Code Snippet 3, but the packet size is different (350 vs. 204), and we also have a new packet sent to the SqlSatellite with a size of 6300. Let’s start with the last portion first; the packet with the size of 6300.

This packet actually contains the data sent to the SqlSatellite (the data represented by the @input_data_1 variable). Normally when SQL transfers data it is done via the

TDS protocol (Tabular Data Stream). However when sending data to and from the SqlSatellite, TDS is not used, but a custom protocol called BXL (Binary eXchange Language). The BXL protocol is optimized for fast data transfers between SQL Server and external script engines.

In the next blog-post in this series, we’ll look more at the BXL protocol, and why you see a packet size of 6300, when we only retrieve one row, with six int columns.

Let us look at the first question; why is the packet size different when the R script is exactly the same. To try to figure this out, we’ll use a packet analyzer: WireShark.

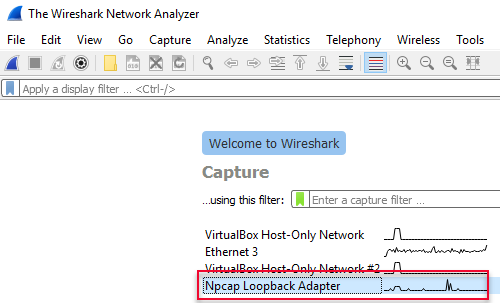

NOTE: If you are running SSMS and SQL Server on the same machine, then you need the Npcap packet sniffer library instead of the default WinPcap. This is because WinPcap doesn’t support loop-back adapters.

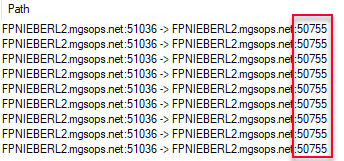

At this stage you don’t need the WinDbg breakpoints, so just disable all the breakpoints, both for SQL Server as well as the launchpad process. Also take note of the port SQL Server listens on for the satellite connection. We need the port number to filter events in WireShark, and we can get the port number by running netstat -o -a -n or look at the Path column in Process Monitor:

Figure 12: Get Port Number from Path

Equipped with the port number, it is time to set up WireShark for packet sniffing. Start WireShark as admin and on the opening screen double click the “Npcap Loopback Adapter”:

Figure 13: WireShark

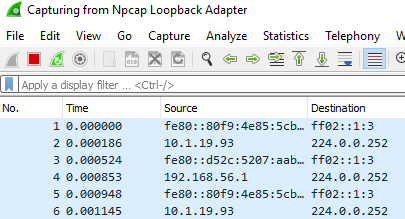

That will now immediately start capturing events:

Figure 14: WireShark Events

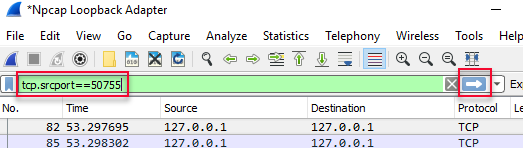

Capturing can be stopped by clicking Ctrl + E, or click on the red square in Figure 14 to the right of the grayed-out shark fin in the tool-bar. What we want to do now is to create a WireShark display filter, so we only see network packets we are interested in. The filter we’ll set is a filter showing only packets originating from the SQL Server’s listening port, as in Figure 12 above. You set the filter in the text box just underneath the toolbox, and the filter you use is tcp.srcport==port_number, you then apply it by clicking on the right arrow to the right the filter box:

Figure 15: WireShark Display Filter

In Figure 15, I set the filter to be tcp.srcport==50755, and then I applied the filter by clicking the arrow. To start using this:

- Clear the Process Monitor display, and make sure you are capturing events.

- Start WireShark capturing (Ctrl+E). If you get a question whether you want to save the captured packets, just click “Continue without Saving”.

- Execute the code in Code Snippet 3.

The Process Monitor output looks almost the same as in Figure 9, whereas the WireShark output looks like so:

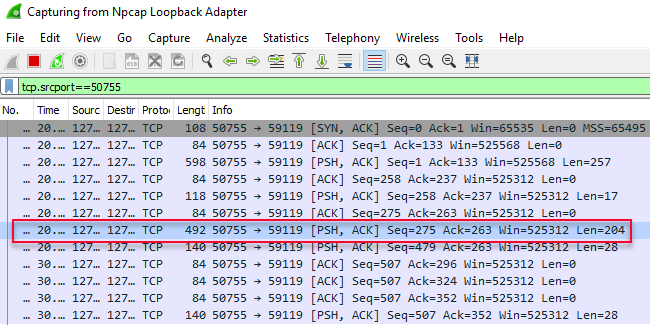

Figure 16: WireShark Captured Packets

WireShark has captured the various packets sent from SQL Server, and we can see the same packages in WireShark as in ProcessMonitor.

NOTE: Actually WireShark has a couple of more packets, as ProcessMonitor doesn’t show some of the

ACKpackets.

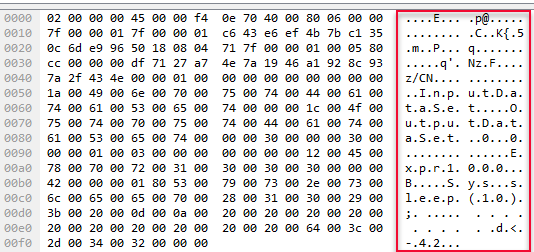

The packet we are interested in is the one that is outlined in red in Figure 16, with a length of 204. Click on it and in the lower pane in WireShark (the packet bytes pane) you will see the data of the packet in a hex-dump style, and on the right hand side the corresponding ASCII text translation:

Figure 17: WireShark Hex-dump

The interesting part in Figure 17 is the ASCII text translation (outlined in red) where we see something that is somewhat readable, and parts of it looks suspiciously like our script. I copied out the ASCII translation (File | Export Packet Dissections | As Plain Text), and this is what it looked like:

|

|

Code Snippet 6: WireShark Packet ASCII Text

In Code Snippet 6 we see how our script (S.y.s...s.l.e.e.p.(.1.0.).;. ..... . . . . . . . . . .d.<.-.4.2...) is actually sent to the SqlSatellite. What is then the part of the text saying E.x.p.r.1.0.0.0...B, and why is the length of the packet sent to SqlSatellite different between Code Snippet 3 and Code Snippet 5, when the script is the same?

Start a new capture in WireShark and execute the code in Code Snippet 5. After you have executed, choose the packet in WireShark with a length of 350, and look at the ASCII text. In Code Snippet 7 below, we see what it looks like on my machine after I did it:

|

|

Code Snippet 7: WireShark Packet with Input Data ASCII Text

As we see in Code Snippet 7, part of what is sent to the SqlSatellite is also the actual column names/variables for the script.

Finally what we’ll do is to see how a script which expects a resultset coming back, is sent to the SqlSatellite. For this we’ll use the code in Code Snippet 8 below:

|

|

Code Snippet 8: Script with Resultset

The code in Code Snippet 8, sends in two columns col1 and col2 and we expect a resultset back with two columns; TheAnswer and TheDevil. After having executed the code, and looking at the captured packet in WireShark we see something looking like so:

|

|

Code Snippet 9: WireShark Packet for Input and Output

In Code Snippet 9 we see how we are sending to the SqlSatellite, in addition the the script and the input data column names, also the output data columns.

By now it should be clear that SQL Server uses the SqlSatellite socket connection to send both the external script to execute as well as the actual data to the satellite. In following posts we will look at the BXL protocol used to send data to the satellite, and also how data is sent back to SQL Server.

Summary

From previous posts we knew that SQL Server communicates with the launchpad service over named pipes. We also know that there is communication between SQL Server and the SqlSatellite over sockets. We may have assumed that data was sent from SQL Server to the R components through the named pipe connection to the launchpad service, and the on from there to the R components.

In this post we have seen how that is not true, but how both the script to execute including some metadata, as well as the actual data to use for analysis (@input_data_1) is sent over the socket connection.

~ Finally

If you have comments, questions etc., please comment on this post or ping me.

comments powered by Disqus