This is the 19:th post in a series about Microsoft SQL Server R Services, and the 18:th post that drills down into the internal of how it works. To see other posts (including this) in the series, go to SQL Server R Services.

In this post we’ll continue looking at data coming back to SQL Server, and what happens code-wise in SQL.

Recap

In the last few posts in this series, we have looked at what happens when data is being returned to SQL Server from the SqlSatellite.

In Internals - XVI we looked at the data packages coming back to SQL Server, and realized there were two:

- One small:ish

- One large.

We subsequently saw that the small packet held meta data about the columns being returned and the large packet held the actual data. The reason for the packet being large was due to the data being treated as originating from nullable columns, so quite an overhead was put onto the various columns. This is similar to what we discussed in Internals - XIV.

Internals - XVII talked about what happens inside SQL Server when data is being returned, e.g. what the code flow looks like. We saw how, after the data packet(s) were sent to the SqlSatellite:

- Immediately

sqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript::PullRowwas called, and waited to be signaled when data was returned. - The schema of the returning data was determined by calls to

sqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript::ProcessOutputSchema,sqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript::GetOutputSchema,sqllang!CServerCargoContext::ReadSchemaInternal, andsqllang!CServerCargoContext::ReadSchemaFromPacket. - The result rows were processed, and turned into TDS packets, by calls to

ProcessResultRows(oneProcessResultRowsper row). - During the first

ProcessResultRowsan ack packet is sent to the SqlSatellite and two packets is being returned. - A final

ProcessResultRowswas called to indicate that no more rows are coming.

There was a question what the two packets returned to SQL Server after the ack packet did, and we “sort of” realized that one of the packets indicated that no more data was coming from the SqlSatellite. The other packet we did not know what it did.

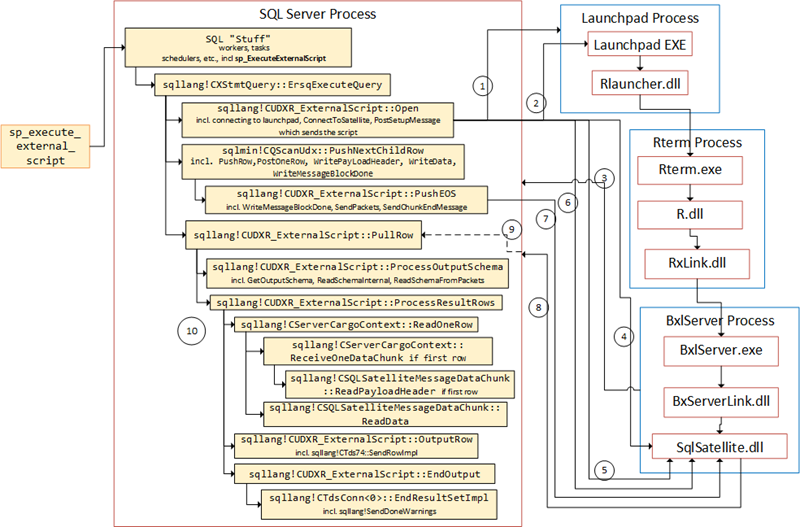

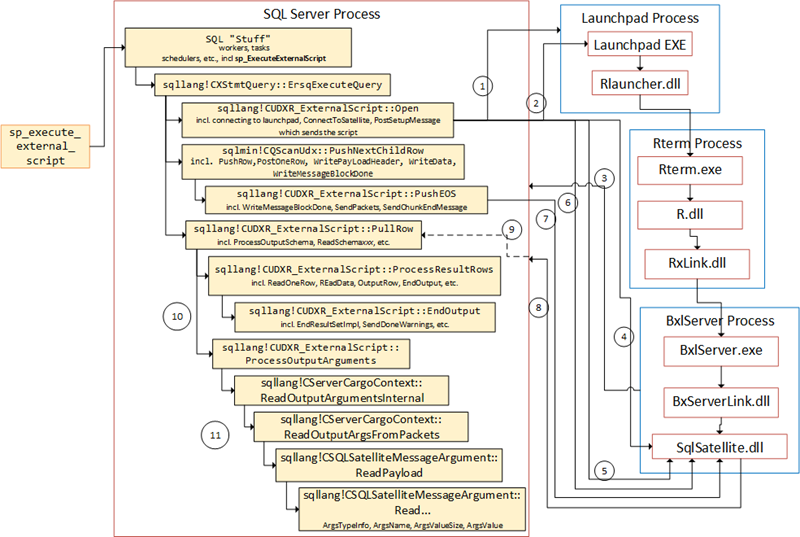

To illustrate the code flow we had a figure like so:

Figure 1: Code Flow Receiving Data from SqlSatellite

The numbered arrows shows the communication out to and in from SQL Server, and in what order it happens:

- SQL Server opens named pipe connection to the launchpad service.

- Message sent to the launchpad service.

- After the call above, the SqlSatellite opens a TCP/IP connection to SQL Server.

- SQL Server sends the first packet to the SQL Satellite for authentication purposes.

- A second authentication packet is sent to SqlSatellite.

- The script is sent from inside

sqllang!CSatelliteProxy::PostSetupMessage - The data for

@input_data_1is sent together with two end packets. - Packet are coming back to SQL Server containing meta-data and the actual data.

PullRowis being signaled.- Execution continues to process meta-data as well as result rows.

Housekeeping

Housekeeping in this context is talking about the tools we’ll use, as well as the code. This section is here here for those of who want to follow along in what we’re doing in the posts.

Helper Tools

To help us figure out the things we want, we will use Process Monitor, WinDbg, and WireShark:

- Process Monitor, will be used it to filter TCP traffic. If you want to refresh your memory about how to do it, we covered that in Internals - X as well as in Internals - XIV.

- In the last few posts I have used WinDbg preview a my debugger, but in this post I am reverting back to WinDbg “classic”. If you need help with setting it up, that is covered in Internals - I.

- I’ll use WireShark for network packet sniffing. In previous posts I have used Microsoft Message Analyzer for this, but I am now back to WireShark as I find it gives me more readable output. If you want a refresher about WireShark, we covered the setup etc., in Internals - X.

Code

The code below sets up the database and creates some tables with some data. It is more or less the same as we’ve used in the last posts:

|

|

Code Snippet 1: Database, and Database Object Creation

The code we’ll use should by now look very familiar:

|

|

Code Snippet 2: Base Code to Execute

In previous posts, the script has also contained a Sys.sleep, but for now it is not necessary - we may change the script further down and include Sys.sleep, or we may not :).

WITH RESULT SETS

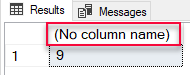

Up until now, when we have executed code where data comes back from the SqlSatellite, the result looks something like so:

Figure 2: Undefined Column Name

From Figure 2 we see the result, but with no column name. That’s because the SqlSatellite (or the R engine for that matter) doesn’t know about column names, or - at least - doesn’t take them into account. So, if you wanted the columns in the return result-set to be named in a specific way, you’d have to use the WITH RESULT SETS <result_sets_definition>:

|

|

Code Snippet 2: Defining Output

The WITH RESULT SETS in Code Snippet 2 tells SQL server that the one column being returned from the SqlSatellite, should be named Column1 and be treated as an int. Executing the code in Code Snippet 2, results in the following:

Figure 3: Result with Column Name

Having defined WITH RESULT SETS we see now in Figure 3 how the one column is named Column1. However, this post (or section in this post) doesn’t really have anything to do with WITH RESULT SETS, but what happens inside the SQL Server engine when a result-set comes back from the SqlSatellite and WITH RESULT SETS is set.

NOTE: Almost all examples you see of

sp_execute_external_scriptincludeWITH RESULT SETS. As we have seen in previous posts as well as this,WITH RESULT SETSis not required. If you want to read more aboutWITH RESULT SETSspecifically, there is a link here.

Ok, so let’s find out what happens - and where - when a result-set comes back from SqlSatellite, with WITH RESULT SETS is defined. Here’s what we’ll do:

- Run WinDbg as admin.

- Attach WinDbg to the SQL Server process (

sqlservr.exe) - DO NOT DO THIS ON A PRODUCTION SERVER. - Enable an Event Filter, in WinDbg for

C++ EH Exception. If you need to refresh you memory about how to do it, Internals - II goes into the details. - Change the

WITH RESULT SETSin Code Snippet 2 to:WITH RESULT SETS ((Column1 int, ExtraColumn int )).

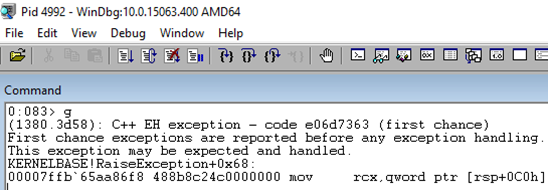

By adding an extra column to the result-set definition, an exception will occur when executing - as the number of columns in the definition has to match exactly what is being returned. The idea is that we’ll then be able to to break in the debugger where the exception happens and investigate the call-stack, to be able to see where we break. So now we can execute the altered code, and sure enough an exception happens:

Figure 4: C++ EH Exception

From Figure 4 we see how we have stopped execution at the point of the exception. This gives us now the ability to check the call-stack: k:

|

|

Code Snippet 3: Call Stack at Exception

The code in Code Snippet 3 shows the abbreviated call-sack at the time of the exception, and we see some routines that we also saw in Internals - XVII as well as in the Recap above:

sqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript::PullRowsqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript::ProcessOutputSchemasqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript::BeginOutput

One routine we haven’t seen before though is the sqllang!CExecWithResultSetsCOut::SendMetaImpl, and it is this routine that handles the WITH RESULT SET. We can verify that this is the case by setting a breakpoint at SendMetaImpl and execute the code in Code Snippet 2 (without the extra column in the result set definition). We see how the execution breaks at the break-point. If we were to execute without any result set definition, the break-point wouldn’t be hit.

The WITH RESULT SETS is not specific to sp_execute_external_script but was introduced in SQL Server 2012 as a way to “reformat” a result-set, and can be used whenever EXECUTE is called. Let’s say we have code like so:

|

|

Code Snippet 4: sp_executesql with Result Set Definition

If the breakpoint we set above is still enabled, we’ll see how we break when we execute the code in Code Snippet 4.

So from all of the above, when we are defining a result set definition for data being returned from the SqlSatellite, we see how the processing is handled in:

|

|

Code Snippet 5: Routines Involved with Result Set Definition

So that is WITH RESULT SETS. What about output parameters?

Output Parameters

So far in previous posts as well as in this- we have discussed what happens when result sets come back from the SqlSatellite, and we should be fairly confident now in understanding what happens in SQL Server. However, result-sets are not then only thing we can get back, we can also get back output parameters and in this section we’ll have a look at how that works.

This is some of the code we’ll use:

|

|

Code Snippet 6: Base Code for Output Parameters

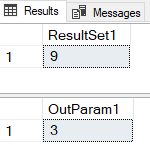

As you see in Code Snippet 6, there is one output parameter @a which in the script is assigned to a value of 3. When we execute the code, the result is:

Figure 5: Result and Output Parameter

Output Parameter Packets and Content

Let’s see how output parameters are handled:

- Run Process Monitor as admin and load the filter we used in

Internals - XVI where we filtered for

TCP SendandTCP ReceiveforBxlServer.exe. - Execute the code in Code Snippet 6 and look at the output from Process Monitor.

- Pay attention to the

Pathcolumn in the output, as it shows - as last part - what port SQL Server listens on. We’ll use that later when doing WireShark packet sniffing.

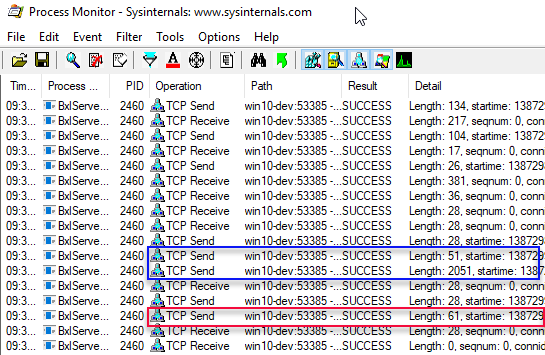

The output looks something like so:

Figure 6: Result and Output Parameter

What we see in Figure 6 is what we have seen a few times before: we see the two data packets coming back from SQL Server (lengths: 51, 2051), followed by the ack message sent from SQL Server, followed by the two packets coming back from the SqlSatellite. We believe that one of the packets is indicating end of result-set, but we don’t know what the other packet is for. But wait a second, normally (with no output parameters) the second packet coming back after the ack message has a length of 28 - now, the packet (outlined in red) has a length of 61! What if we were to execute and expect back two output parameters (both int):

|

|

Code Snippet 7: Code for 2 Output Parameters

The output from Process Monitor when executing the code in Code Snippet 7 will show that the second packet (the one with a length of 61 above), now has a length of 94. With three int output parameters the length will be 127. So that particular packer definitely has something to do with output parameters, and for each new output parameters (of type int and a short parameter name) an additional 33 bytes are added to the packet. Seeing that with no output parameters the packet length was 28 bytes, so it would would make sense to assume that the output parameter packet has an overhead of 28 bytes (61 - 33 = 28).

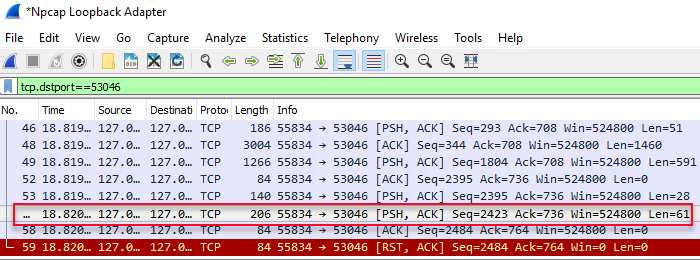

To try and figure out what happens we’ll switch over to WireShark, and do some packet sniffing:

- Run WireShark as admin.

- Choose the network adapter to “sniff” on. See Internals - X for discussion around loop-back adapters etc.

- Set a display filter on the port SQL Server listens on. In this case we want to sniff incoming packets, so the filter should be:

tcp.dstport==xyz(xyzis the listening port of SQL Server). - Apply the filter.

When we execute the code in Code Snippet 6 the output in WireShark will be:

Figure 7: Result and Output Parameter

In Figure 7 we see some of the packets being received by SQL Server from the SqlSatallite, and the packet outlined in red is the one we are interested in (length of 61). When looking the data part of the packet (the 61 bytes) as a hex-dump it looks like so:

|

|

Code Snippet 8: One Output Parameter Packet

What we see in Code Snippet 8 is the “raw” hex dump (with ASCII hex on the right). Let’s see if it can be made somewhat more readable:

|

|

Code Snippet 9: Formatted One Output Parameter Packet

I have tried to “finesse” the packet in Code Snippet 9 by breaking it up in a “header” part, which is the first 28 bytes and a “payload” part. I have also taken the ASCII hex and tried to make it more readable. What we see from Code Snippet 9 is something like this:

- The parameter name is in the packet as double byte characters. It is human readable in the ASCII hex representation where it starts at byte 21 in the “payload”, and you can see it in the hex dump as well at byte 21:

40 00 61 00(@a). - The value of the parameter starts at byte 29 in the payload: hex

03 00 00 00. - It looks like there is an “end” byte, hex

01at the end of the packet, or at least at the end of the data that defines the parameter. - There are 4 bytes between the end of the parameter name, and where the value is.

Let’s see if we can further confirm what we see in Code Snippet 9, by executing the code in Code Snippet 7 and capture the packets in WireShark. :

|

|

Code Snippet 10: Formatted Two Output Parameters Packet

As you see in Code Snippet 10, I have broken up the packet in three parts; “header” and one “payload” per parameter. I did it as, when looking at the “raw” packet, it was obvious that each parameter started with hex 38 00 00 00 and ended with hex 01. So Code Snippet 10 confirms our assumptions above. It also shows another interesting thing: look in the “header” at the last four bytes. In Code Snippet 9 the value was hex 01 00 00 00, which is decimal 1, and in Code Snippet 10 it is hex 02 00 00 00, decimal 2. Is it a coincidence that the number of parameters in Code Snippet 9 was 1, and in Code Snippet 10 2? I do not think so, as when I tested with more parameters those 4 bytes always showed the number of parameters being returned.

SQL Server Code

Now when we know where the output parameters come back and what the packets look like, let’s look at at what happens inside SQL Server when that output parameter packet comes back.

In

Internals - XVII we looked for interesting routines in x sqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript* for handling rows coming back from the SqlSatellite. Let’s do the same for output arguments:

- Start up WinDbg as admin - once again, DO NOT DO THIS ON A PRODUCTION SERVER.

- Attach to the SQL Server process.

- Execute in the WinDbg console:

x sqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript*Process*Arguments*

The execute statement results in one routine: sqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript::ProcessOutputArguments, and - if I may say so myself - it looks like we’re onto something here. To confirm we’re on the right track, set a breakpoint at sqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript::ProcessOutputArguments and change the code in Code Snippet 6 to have a Sys.sleep in the script so we can better determine what is being called when:

|

|

Code Snippet 11: Base Code for Output Parameters with Pause

Execute the code in Code Snippet 11, and when the breakpoint is hit (after the sleep), check the call-stack: k:

|

|

Code Snippet 11: Call Stack Leading up to ProcessOutputArguments

Aha, Code Snippet 12 show how ProcessOutputArguments is part of PullRow which we looked at in

Internals - XVII, and which we mentioned in the Recap above. If we look back at PullRow, a very, very abbreviated call-stack looked like so:

|

|

Code Snippet 12: Highly Abbreviated PullRow Call Stack

Looking at the PullRow call-stack in Code Snippet 12, the question is where ProcessOutputArguments fit in? The call-stack in Code Snippet 11 shows how ProcessOutputArguments is called directly from PullRow, so is that before or after ProcessResultRows? To figure this out, what do we do - well, we’ll set a breakpoint at sqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript::ProcessResultRows, in addition to the breakpoint at ProcessOutputArguments. When we execute we see that ProcessResultRows is called twice, followed by ProcessOutputArguments. From that we can say that the call-stack also including ProcessOutputArguments looks something like so:

|

|

Code Snippet 13: Highly Abbreviated PullRow Call Stack Including ProcessOutputArguments

We could have reached the same conclusion as we came to in Code Snippet 13 if we had had a look at the “trace and watch” file we did in

Internals - XVII for PullRow: pull_row_full.txt.

NOTE: If you wonder why there are two

ProcessResultRowscalls when only one row is coming back - go back up to the Recap, where it is explained.

To finish off with, let’s see what happens inside ProcessOutputArguments:

- Disable the

ProcessResultRowsbreakpoint, but keep theProcessOutputArgumentsbreakpoint. - Execute the code in Code Snippet 11 (the one with

Sys.sleep). - When the

ProcessOutputArgumentsbreakpoint is hit, do a “trace and watch”:wt -l4(trace 4 levels deep).

When the trace has finished you can copy it to a file, to make it easier to follow what happens. When looking at the file, we see something like this:

|

|

Code Snippet 14: *Routines During ProcessOutputArguments

From Code Snippet 14 we see how the argument packet is being read, from there we read the type information, followed by the argument name and value. If there are more than one output argument, the do it all over again. Oh, and if there are no output parameters we “bail” out after the ReadPayload routine.

Summary

In this post we have looked at what happens if we have a result set definition when executing sp_execute_external_script. We saw that the result set definition was handled during sqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript::ProcessOutputSchema and the routine that did this was sqllang!CExecWithResultSetsCOut::SendMetaImpl. The SendMetaImpl is used not only for external scripts but for all executions with result set definitions.

We then went on to how output parameters are handled and we started looking at where the parameters are returned and what the packet looked like:

- The output parameters is being returned in the second packet coming back from the SqlSatellite after the ack packet has been sent to the SqlSatellite.

- The packet returning the output parameters has a 28 bytes “header”.

- The header contains the number of parameters being returned.

- There is one “payload” per output parameter.

- The parameter “payload” contains the name of the output parameter as double byte characters.

- The payload consists of 20 bytes before the name of the parameter.

- After the parameter name is 4 bytes.

- The 4 bytes are followed by the parameter value.

- At the end of the parameter payload is an “end” byte, hex

01. - The size of the value is the data type size for numerics, and storage size for alpha-numerics.

- For alpha-numerics there are 2 bytes pre-pending the value. These 2 bytes indicate the size.

An example of this would be what we receive if we were to execute the following:

|

|

Code Snippet 15: Two Output Params: Integer and Varchar

The code in Code Snippet 15 reults in two output parameters: one - int - with a value of 3, and the other - varchar - with a value of “abcd”. The output parameter packet looks something like so after I have formatted it a bit:

|

|

Code Snippet 16: Output Parameter Packet

As you see in Code Snippet 16, I have separated the “header” from the “payload”, and also made the hex somewhat more readable by separating out the various parts we discussed above.

When output arguments are returned to SQL Server, they are handled by the sqllang!CUDXR_ExternalScript::ProcessOutputArguments routine which is part of the PullRow call. I have taken the Figure 1 in the recap and altered it to show the flow for output arguments:

Figure 8: Code Flow Receiving Output Arguments from SqlSatellite

The numbered arrows shows the communication out to and in from SQL Server, and in what order it happens, there is not much of a difference from what is in the Recap, except for the added point 11:

- SQL Server opens named pipe connection to the launchpad service.

- Message sent to the launchpad service.

- After the call above, the SqlSatellite opens a TCP/IP connection to SQL Server.

- SQL Server sends the first packet to the SQL Satellite for authentication purposes.

- A second authentication packet is sent to SqlSatellite.

- The script is sent from inside

sqllang!CSatelliteProxy::PostSetupMessage - The data for

@input_data_1is sent together with two end packets. - Packet are coming back to SQL Server containing meta-data and the actual data.

PullRowis being signaled.- Execution continues to process meta-data as well as result rows.

- After processing result rows, output arguments are processed.

~ Finally

If you have comments, questions etc., please comment on this post or ping me.

comments powered by Disqus